Neurobehavioral & Cognitive Disorders

Transient global amnesia

Jul. 19, 2024

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

The topic of alcohol abuse related to acute and chronic exposure covers a wide spectrum of neurologic syndromes involving the central and peripheral nervous system. Historical perspectives, clinical manifestations, clinical vignettes, etiology, pathogenesis, pathophysiology, epidemiology, prognosis, complications, and management are all discussed in this updated article. In addition, the authors discuss select mechanisms of cellular injury by alcohol.

|

• Alcohol intoxication has an acute and chronic symptomatology. | |

|

• The lethal dose of alcohol varies widely and depends on many external and internal factors. Tolerance develops with repeated exposures. | |

|

• Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is particularly found in the alcoholic population. | |

|

• Alcohol affects almost all areas of the nervous system. | |

|

• Alcohol affects the functioning of many systems in the body (heart, liver, muscle, nerve). |

Humans have consumed alcohol for thousands of years. Indeed, archaeologists have found evidence of nearly 11,000-year-old beer brewing troughs at a site in Turkey called Göbekli Tepe (69).

The term “alcoholism” was first used by a Swedish physician in 1849 to describe the adverse systemic effects of alcohol. Also, early psychiatry texts described a syndrome of alcohol-related deterioration characterized by intellectual and behavioral abnormalities (11).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-Tr) defined alcoholism as “maladaptive pattern of drinking, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress” (12).

The definition of alcoholism by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and the American Society of Addiction Medicine is “a primary, chronic disease characterized by impaired control over drinking, preoccupation with the drug alcohol, use of alcohol despite adverse consequences, and distortions in thinking” (193).

The role of alcoholism in the development of cognitive and functional decline was known in Ancient Greece (132) and has received serious study in Western medicine for more than 250 years.

In Greek mythology, Silenus was the frequently drunken companion and tutor of the wine god Dionysus. Artistic depictions of the drunken Silenus show him supported by satyrs or carried by a donkey.

Some Renaissance artistic depictions of the drunken Silenus show features of alcoholic cirrhosis, perhaps most fully in the painting Drunken Silenus (1626) by Spanish painter Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652): evident signs of liver disease in this painting include parotid gland swelling, spider angioma (left parasternal area), gynecomastia, and ascites.

A clinic-pathologic description of hepatic encephalopathy from alcoholic cirrhosis was described by Italian anatomist and pathologist Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771), Professor of Anatomy at the University of Padua, in his De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis (Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy) (192).

Alcoholic neuropathy was documented at least as early as 1787 by English physician and philanthropist John Coakley Lettsom (1744-1815) (171), but other neurologic complications of alcoholism were probably not recognized until the end of the 19th century or later.

Alcohol-related deficits in memory and intellectual ability were reported in 1878 by British psychiatrist Robert Lawson (1846-1896) of the Wonford House Lunatic Asylum in Exeter (167; 166).

Subsequently, in a series of three articles from 1887 to 1889, Russian neuropsychiatrist Sergei Sergeievich Korsakoff (sometimes spelled Korsakov; 1853/1854-1900) gave a comprehensive description of the persistent amnestic confabulatory state now known as Korsakoff psychosis, occurring in conjunction with peripheral polyneuropathy, a combination he initially labeled either as “psychosis associated with polyneuritis” or “polyneuritic psychosis” (152; 151; 150; 309; 304; 305; 303; 159; 162; 163). Korsakoff based his conclusions on at least 46 patients, about two-thirds of whom were alcoholics, whereas the remainder suffered from a diverse group of disorders associated with protracted vomiting.

Korsakoff was apparently unaware of the syndrome incorporating a confusional state, ophthalmoparesis and other oculomotor findings, ataxia, and neuropathic features, which had been described by German neuropsychiatrist Carl Wernicke (1848-1905) in 1881 and labeled as “Die acute, hämorrhagische Poliencephalitis superior” (acute hemorrhagic superior polioencephalitis) and is now generally called Wernicke encephalopathy (314; 145; 146). The clinico-pathologic overlap between Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff psychosis was ultimately recognized in the late 1920s and early 1930s (92; 134; 42), and the two terms became linked as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

The term “alcoholic hallucinosis” (also known as “alcohol hallucinosis” and “alcohol-related psychotic disorder”) refers to a disorder of acute onset, with a predominance of auditory hallucinations (although delusions and hallucinations in other sensory modalities may also be present), no disturbance of consciousness, and a history of heavy alcohol consumption (96).

This syndrome has often been attributed to Swiss psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleuler (1857-1939), who labeled it alcoholic hallucinosis (Alkoholhalluzinose) and considered it as an alcoholic madness (Alkoholsahnsinn) (31); Bleuler was also responsible for other psychiatric terms, including schizophrenia, schizoid, and autism. However, in his textbook, Bleuler acknowledged the earlier description by Wernicke, who labeled the disorder as “chronic hallucinosis in alcoholism” (chronische Halluzinose beim Alkoholismus) (315). Even earlier, in 1847, the French author Claude-Nicolas- Séraphin Marcel described a similar symptom complex under the label of folie d'ivrogne (ie, drunken madness) (181).

Although alcoholic intoxication was long recognized in art, portrayals of delirium tremens in caricatures (276) and health propaganda posters became particularly prominent in the early 20th century, in the years before and during Prohibition (1920-1933) in the United States.

Marchiafava-Bignami disease is a progressive alcoholism-related neurologic disease characterized by corpus callosum demyelination and necrosis and subsequent atrophy. The disease was first described in 1903 by the Italian pathologists Ettore Marchiafava (1847-1935) and Amico Bignami (1862-1929) in an Italian Chianti drinker (182). In the autopsy of this patient, the middle two-thirds of the corpus callosum were necrotic.

In the last century, through careful observation and description, American neurologist and neuropathologist Raymond Delacy (“Ray”) Adams (1911-2008) made the most prodigious contributions in understanding the neurologic complications of alcohol abuse, in conjunction with various protégés, notably Boston-born neurologist Joseph Michael (“Joe”) Foley (1916-2012) and, subsequently, Canadian-American neurologist Maurice Victor (1920-2001) (01; 02; 03; 04; 86; 05; 306; 305; 307; 301; 308). Foley began to work with Adams on the neurologic manifestations of liver disease in the late 1940s after Foley returned from his military service during World War II (165; 160). In a series of reports from 1949 to 1953, Adams and Foley described the clinical (neurologic), electroencephalographic, and neuropathologic features of alcoholic liver disease, including the clinical and electrophysiologic features of asterixis (01; 02; 03; 04; 86).

Social commentary on the neurologic degeneration and social decay from alcoholism. The neurologic disorders and social decay resulting from alcoholism were targeted by social reformers in many countries since at least the 18th century.

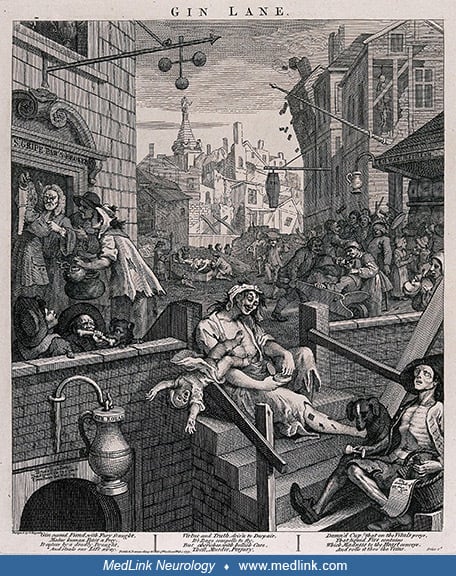

English engraver, pictorial satirist, and social critic William Hogarth (1697-1764) depicted the effects of alcoholism in his famous engraving, Gin Lane (1751).

Hogarth's engraving, published according to Act of Parliament on February 1, 1751 in support of what would become the "Gin Act," shows a poor London street (the area depicted is St. Giles, London) strewn with hopeless drunka...

Hogarth's engraving, published according to Act of Parliament on 1 February 1751 in support of what would become the "Gin Act," shows a poor London street (the area depicted is St. Giles, London) strewn with hopeless drunkards and lined with gin shops and a flourishing pawnbroker. The inhabitants of Gin Lane are being destroyed by their addiction to the foreign spirit of gin, with the engraving illustrating shocking scenes of child neglect, starvation, madness, drunken brawls, and death. Hogarth's illustration is filled with satirical humor: the pawnbroker's shop depicted is "S. Gripe pawnbroker;" the distillery is "Kilman distillery;" a gin shop sign reads "drunk for a penny, dead drunk for two pence, clean straw for nothing;" and a drunkard's paper is headed "the downfall of Mdam. gin."

A poem below the engraving reads as follows:

|

Gin cursed Fiend, with Fury fraught, Virtue and Truth, driv'n to Despair, Damn'd Cup! that on the Vitals preys, |

At that time, there was no quality control whatsoever, and gin was frequently adulterated (eg, with turpentine). When it became apparent that copious gin consumption was causing social problems, social reformers and the government made efforts to control the production of the spirit. The Spirit Duties Act (commonly known as the Gin Act of 1736) imposed high taxes on sales of gin, forbade the sale of gin in quantities of less than two gallons, and required an annual payment of £50 for a retail license. These measures had little effect beyond increasing smuggling and driving the distilling trade underground. The act was repealed by the Gin Act of 1743, which set much lower taxes and fees.

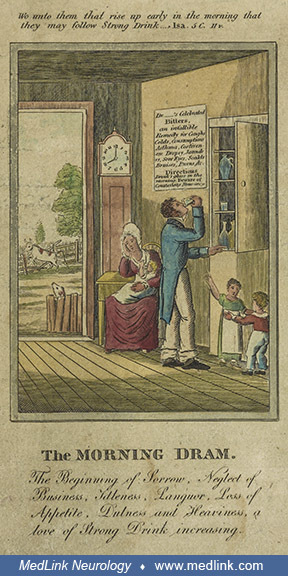

Similarly, the 4-part sequence of "A Drunkard's Progress" (1826) by American engraver and historian John Warner Barber (1798-1885) depicts the neurologic and social decay from alcoholism, complete with biblical admonitions. In the first image, "The Morning Dram," the father is drinking at 8 AM, ignoring his wife and children.

Hand-colored engraving by John Warner Barber (1798-1885), printed in New Haven, Connecticut. Biblical quotation above the image: "Wo unto them that rise up early in the morning that they may follow Strong Drink... Isa 5 C. 11v....

In the second image, "The Grog Shop," two men are drinking at a saloon, while two are brawling, one is vomiting, and one is unconscious on a bench.

Hand-colored engraving by John Warner Barber (1798-1885), printed in New Haven, Connecticut. Biblical quotation above the image: "Wo unto them that are mighty to drink wine, and men of strength to mingle Strong Drink... Isaiah ...

In the third image, "The Confirmed Drunkard," the father is intoxicated on the floor, while his wife and children are afraid, and the home is falling apart.

Hand-colored engraving by John Warner Barber (1798-1885), printed in New Haven, Connecticut. Biblical quotation above the image: "Who hath wo? Who hath sorrow? Who hath contentions? Who hath wounds without cause? ... They that ...

In the final image of the sequence, "Concluding Scene," there is an auction sign on the house, ordered by the sheriff. The family is evicted and departing with the wife in tears.

Hand-colored engraving by John Warner Barber (1798-1885), printed in New Haven, Connecticut. Biblical quotations above the image: "The drunkard shall come to poverty. Proverbs 23 Chap. 21 v." [Proverbs 23:21] and "The wages of ...

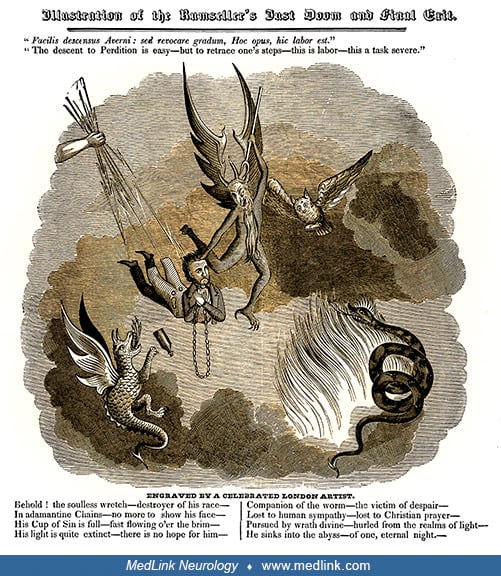

Social critics and reformers blamed both the alcoholic and those that manufactured or sold alcohol for the adverse outcomes on individuals and society. The responsibility of purveyors of alcohol for the negative effects was portrayed in various ways, but often with religious overtones. For example, the engraving titled "Illustration of the Rumseller's just doom and final exit" (1835).

A Latin expression serves as an epigram: "Facilis descensus Averni: sed revocare gradum, Hoc opus, hic labor est." ("The descent to Perdition is easy—but to retrace one's steps—this is labor—this a task severe.") The engraving depicts a man who is praying the rosary, about to be impaled by the devil, and struck by lightning bolts held in the hand of God. He is descending into Hell, portrayed by fire, smoke, a snake, and a fire-breathing serpent or dragon. A poem below the engraving reads as follows:

|

Behold! the soulless wretch—destroyer of his race— Companion of the worm—the victim of despair— |

Leading up to Prohibition in the United States, numerous forms of propaganda were used to convince people of the harms of alcohol (or of its relative safety by opponents of prohibition). One political cartoon of that era, "A sample room and its samples" (1902), for example, depicted a saloon keeper in front of a morbid saloon window display.

The window display sign says: "SHOW WINDOW EXHIBIT. WHAT OUR LIQUORS CAN DO. GENUINE SPECIMENS MADE ON THE PREMISES." The implications of this sign are displayed in the window in the form of five people damaged by alcohol, four of whom are labeled with their alcohol-induced problems: madman, tramp, convict, and idiot child (fetal alcohol syndrome). The fifth person, a woman, appears depressed or confused.

The 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution banned the manufacture, transportation, and sale of intoxicating liquors. The Volstead Act was ratified by the states on January 16, 1919 and went into effect on January 17, 1920, marking the beginning of the period in American history known as Prohibition. Despite an army of agents of the Bureau of Prohibition, Prohibition proved difficult to enforce; eventually, the illegal production and sale of liquor (“bootlegging”), the proliferation of illegal drinking spots ("speakeasies"), and the accompanying rise in gang violence and other crimes led to waning support for Prohibition by the end of the 1920s.

The 21st Amendment was ratified on December 5, 1933, repealing the 18th Amendment and ending Prohibition.

|

• Based on the temporal relationship between alcohol abuse and onset of neurologic symptoms, the diverse neurologic manifestations of alcohol abuse may be subdivided into three main categories: (1) acute intoxication; (2) a withdrawal syndrome from sudden abstinence; and (3) a varied group of acute, subacute, or chronic disorders secondary to chronic alcohol abuse. | |

|

• In contrast to the acute and (usually) reversible pharmacological effects of ethanol intoxication, prolonged alcohol abuse leads to persistent and potentially irreversible neurologic deficits, potentially affecting any level of the nervous system. | |

|

• Alcohol withdrawal seizures usually occur after years of alcohol abuse with a single generalized tonic-clonic seizure or a brief cluster of such seizures occurring 6 to 48 hours after the last drink. | |

|

• Alcohol withdrawal seizures typically occur as blood alcohol approaches zero, or shortly thereafter, and are rarely seen after more than 2 days of abstinence. | |

|

• The initial phase in Wernicke encephalopathy is classically characterized by the triad of mental confusion, oculomotor disturbance, and gait ataxia. | |

|

• Oculomotor disturbances in Wernicke encephalopathy can include nystagmus, abducens or conjugate gaze palsies, and ptosis. | |

|

• Wernicke encephalopathy may progress to hypotension, stupor, coma, hypothermia, and death if the underlying thiamine deficiency is unrecognized or untreated. | |

|

• Approximately 80% of untreated Wernicke encephalopathy patients subsequently evolve to a Korsakovian state. | |

|

• The Korsakoff syndrome is a memory disorder that typically emerges as the acute symptoms and signs of Wernicke encephalopathy subside; the amnesia is characterized by an inability to recall events for a period of a few years before the onset of illness (retrograde amnesia) and an inability to learn new information (anterograde amnesia). | |

|

• The common manifestations of alcoholic pellagra are encapsulated in “the four Ds”: diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death. | |

|

• Most commonly, hepatic encephalopathy is a chronic disorder that occurs in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis with portosystemic shunts. | |

|

• Hepatic encephalopathy has a wide range of presentations progressing successively through stages: (1) unimpaired cognitive function with intact consciousness; (2) lethargy and confusion or delirium; (3) somnolence and disorientation; and (4) coma. | |

|

• Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration is a disorder of progressive cerebellar degeneration that can be seen in patients with severe alcoholism; it preferentially affects the anterior and superior vermis, giving rise to a remarkably stereotypic syndrome of ataxic stance and gait. | |

|

• In acute alcoholic myopathy, massive muscle injury triggered by acute alcohol abuse may result in multiple organ failure and death, but alcoholic rhabdomyolysis generally has a good prognosis if renal failure is avoided or is aggressively treated. | |

|

• With chronic alcoholic myopathy only half of the sober patients recovered to normal strength over 5 years, indicating that chronic alcoholic myopathy is only partially reversible. | |

|

• Secondary disabilities (eg, school dropouts, criminal behavior, and substance or alcohol abuse problems) are common in young adults with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. |

The effects of alcohol on the central and peripheral nervous system are varied, and overuse of alcohol can have serious medical and neurologic consequences, even death.

Based on the temporal relationship between alcohol abuse and the onset of neurologic symptoms, the diverse neurologic manifestations may be subdivided into three main categories: (1) acute intoxication; (2) a withdrawal syndrome from sudden abstinence; and (3) a varied group of acute, subacute, or chronic disorders secondary to chronic alcohol abuse.

Acute alcohol intoxication. Ethanol enters and distributes rapidly throughout the body after ingestion. Intoxication occurs because ethanol readily crosses the blood-brain barrier. It acts directly on neuronal membranes and interacts with numerous neurochemical receptors. Behavioral effects may include euphoria, dysphoria, social disinhibition, drowsiness, belligerence, and aggression. In nonalcoholic individuals, these may occur at serum concentrations as low as 50 to 150 mg per dL. Even a moderate dose of alcohol substantially impairs prospective memory function (73). Lethargy, stupor, coma, or death from respiratory depression and hypotension occur at progressively higher concentrations. The lethal dose varies widely because tolerance develops with repeated exposures. Some alcoholics may appear sober at a serum level as high as 500 mg per dL; whereas this same level can be fatal in nonalcoholic individuals.

Chronic alcohol abuse. In contrast to the acute and (usually) reversible pharmacological effects of ethanol intoxication, prolonged alcohol abuse leads to persistent and potentially irreversible neurologic deficits, potentially affecting any level of the nervous system (51; 68). The sites of neuronal injury and, hence, the clinical presentations are governed by genetic, nutritional, and other environmental factors. Individuals with alcohol use disorder typically have impaired memory and smaller precentral frontal and hippocampal volumes (80). Neurologic disorders in individuals with chronic alcohol abuse may occur in isolation, or, more commonly, multiple syndromes may be present in a single patient.

Alcohol withdrawal. Sudden cessation of drinking in a chronic alcoholic typically produces a withdrawal syndrome of central nervous system hyperexcitability and may, if very severe, produce delirium tremens. The earliest symptom is a generalized tremulousness. Insomnia, agitation, delirium, hallucinations (auditory, visual, or tactile), or other perceptual disturbances may follow. The syndrome is also characterized by autonomic hyperactivity, such as tachycardia, profuse sweating, hypertension, and hyperthermia. Withdrawal symptoms commonly begin 6 to 8 hours after abstinence and are most pronounced 24 to 72 hours after abstinence.

Alcohol withdrawal in a postsurgical setting may cause an increase in surgical complications, a situation demonstrated with elective spinal fusion surgery (107).

Alcohol withdrawal delirium. Alcohol withdrawal leads to a short-lived delirium syndrome and is usually easy to differentiate from the direct effects of alcohol on the brain. However, in some individuals, features of delirium, such as paranoia, auditory hallucinations, and attentional deficits, persist for many months. The etiology of this prolonged and attenuated delirium syndrome is unknown. Benzodiazepines used to treat alcohol withdrawal may also occasionally induce delirium (13).

Alcohol withdrawal seizures. Alcohol withdrawal may lead to tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures, usually after years of alcohol abuse (307). Convulsions typically occur 6 to 48 hours after the last drink and may occur singly or in a brief cluster. Alcohol withdrawal seizures typically occur as blood alcohol approaches zero, or shortly thereafter, and are rarely seen after more than 2 days of abstinence; however, a relative fall in blood alcohol levels during sustained drinking can also sometimes produce withdrawal seizures while blood alcohol levels are still at levels typically associated with intoxication. Unless an underlying neuropathology exists, the seizures are rarely focal. Generally, electroencephalograms on such patients are mildly abnormal and usually revert to normal within a few days. Status epilepticus is rare.

Seizures after an isolated episode of intoxication or after a short binge should suggest the possibility of an underlying seizure susceptibility (eg, from prior cortical trauma) or other contributing factors (additional toxic exposure, hypoxia, electrolyte abnormality, etc.). Similarly, seizures during active heavy drinking or after more than a week without alcohol raises the possibility of pathogenic mechanisms other than withdrawal per se (114).

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is the best example of acquired nutritional deficiency in alcoholism (305). Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff syndrome (or Korsakoff “psychosis”) are successive stages of thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency. Increased metabolic demands, glucose infusion, and sudden resumption of dietary intake after a period of malnourishment are risk factors in precipitating acute symptoms.

The initial phase in Wernicke encephalopathy is classically characterized by the triad of mental confusion, oculomotor disturbance, and gait ataxia. Oculomotor disturbances can include nystagmus, abducens or conjugate gaze palsies, and ptosis (305; 41; 264). The encephalopathy may progress to hypotension, stupor, coma, hypothermia, and death if the underlying thiamine deficiency is unrecognized or untreated (264).

The classic triad is insensitive for the diagnosis of Wernicke encephalopathy (112; 195). In particular, the incidence of oculomotor findings is low in patients later shown to have had Wernicke encephalopathy. Consequently, modified diagnostic criteria have been developed to address the insensitivity of the classic triad. Modified diagnostic criteria for Wernicke encephalopathy require at least two of the following four signs: (1) dietary deficiencies, (2) oculomotor abnormalities, (3) cerebellar dysfunction, and (4) either an altered mental state or mild memory impairment (41).

Unfortunately, Wernicke encephalopathy is frequently underrecognized by clinicians (112), especially when the disorder occurs in settings other than alcohol abuse (267).

Coronal section of cerebral MRI FLAIR sequence showing hyperintense signal change of the mammary bodies in a 66-year-old man with Wernicke encephalopathy complicating prolonged parenteral nutrition. (Source: Slim S, Ayed K, Tri...

Axial section of cerebral MRI FLAIR sequence showing hyperintense signal change of the mammary bodies and periaqueductal gray matter in a 66-year-old man with Wernicke encephalopathy complicating prolonged parenteral nutrition....

In pathological series, there is a consistently high proportion of cases of Wernicke encephalopathy that never had a clinical diagnosis of that condition during life (112; 195; 287; 41): indeed, less than 20% of cases of Wernicke encephalopathy are diagnosed prior to death.

Korsakoff syndrome is a memory disorder that typically emerges as the acute symptoms and signs of Wernicke encephalopathy subside. The amnesia is characterized by an inability to recall events for a period of a few years before the onset of illness (retrograde amnesia) and an inability to learn new information (anterograde amnesia, ie, loss of anterograde episodic memory) (41). Almost all patients have limited insight into their memory dysfunction. Other cognitive deficits may manifest themselves but are mild relative to the amnesia (148). Many, but not all, patients confabulate, a phenomenon that may be due to associated frontal lobe dysfunction (27); confabulation may resolve as frontal lobe function improves. Attention, language, and spatial navigation are usually normal. Although usually subacute in onset, Korsakoff syndrome can develop insidiously without evidence of acute encephalopathy, ataxia, or oculomotor findings (301). Approximately 80% of untreated Wernicke encephalopathy patients subsequently evolve to a Korsakovian state (305).

Alcoholics with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome can be differentiated from those with Wernicke encephalopathy (without Korsakoff syndrome), but the severity and stability of memory loss, regardless of other cognitive deficits (41).

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is generally diagnosed in younger patients rather than those diagnosed with alcohol-related dementia (41).

Alcoholic pellagra. Pellagra has been recognized among alcoholics for more than a century (139; 327). The common manifestations of this disorder are encapsulated in “the four Ds”: diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death (159; 161). The typical cutaneous features of pellagra include peeling, redness, scaling, and thickening of sun-exposed areas (159; 161).

However, the dermatitis of pellagra ranges from obvious scaly erythema to more subtle changes that are often mistaken for the photodamage typically seen in the elderly (from a lifetime of cumulative exposure to solar irradiation). Neuropsychiatric features of pellagra include irritability, depressed mood, fatigue, neurasthenia, and poor attention and concentration (159; 161). In more advanced cases, lethargy, confusion, psychotic symptoms, spastic weakness of the limbs, and Babinski signs may be observed. Other findings may include aversion to bright light, glossitis, and dilated cardiomyopathy (115). A range of other less common medical and neurologic manifestations can also be seen as a result of alcoholic pellagra, either due to the pellagra or the chronic effects of alcohol, including, for example, black urine (from urobilinogen) (52), benign symmetrical lipomatosis (84), peripheral neuropathy (109), paratonia, and various forms of myoclonus (256; 257; 218).

Pellagrous encephalopathy in alcoholics is often overlooked, in part because it is frequently mistaken for alcohol withdrawal delirium or Wernicke encephalopathy (256; Oldham and Novic 2012; 177). Also, because the nutritional disorders of alcoholics are often mixed, alcoholic pellagra may be seen in combination with Wernicke encephalopathy or Marchiafava-Bignami disease, a situation likely to foster diagnostic confusion among clinicians (256; 219; 281).

Marchiafava-Bignami syndrome. Marchiafava-Bignami syndrome is a progressive alcoholism-associated neurologic syndrome of corpus callosum demyelination and necrosis and subsequent atrophy (265). The syndrome is thought to be due to a combination of vitamin B deficiency (including thiamine deficiency), malnutrition, and alcohol abuse (particularly large quantities of red wine) (119). The clinical presentation is varied, and premortem diagnosis was almost impossible before the era of modern neuroimaging (301; 260; 102). Some patients present with slowly progressive psychomotor slowing, incontinence, frontal release signs, and wide-based gait. Dysarthria, hemiparesis, apraxia, or aphasia may be present (144). Occasionally, patients may present in stupor or coma. MRI or CT may reveal lesions in the corpus callosum, anterior commissure, and, less commonly, in the centrum semiovale (202) and lateral frontal cortex (130).

Alcoholic cognitive impairment (alcohol-related brain damage). Chronic alcohol abuse in the absence of nutritional deficiencies or organ failure has also been associated with changes in cognitive abilities in detoxified chronic alcoholics, with deficits in recent memory, visuospatial ability, abstract reasoning, speed of information processing, and novel problem solving (246; 153; 235). Commonly, neuropsychological testing shows a decline in performance IQ but not verbal IQ. Aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia are uncommon. Typically, the degree of impairment is mild-to-moderate, with most patients able to carry out daily activities. Widespread cognitive impairment is best encompassed within "alcohol-related brain damage" or "alcoholic cognitive impairment," with Korsakoff syndrome reserved for those with isolated or disproportionate memory impairment (148).

Alcoholic dementia. Alcohol-induced dementia is a syndrome characterized by deficits in memory and intellectual abilities severe enough to interfere with daily functioning. Although no formal diagnostic criteria have been established, Oslin and colleagues proposed that there must be a clinical diagnosis of dementia that remains at least 60 days after the last exposure to alcohol and a history of excessive alcohol consumption for greater than 5 years (213). This syndrome has multiple etiologies and presents with a range of clinical symptoms and abnormalities. Often, dementia attributed to alcoholism is actually dementia due to other etiologies present in an individual who drinks alcohol (223). There is evidence that extreme quantities of alcohol can cause dementia (36) and that low levels may be somewhat protective against dementia (28; 245) and death (74).

Hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy is a metabolic disturbance associated with liver disease or portosystemic shunting. It is characterized by disturbances of consciousness. Most commonly, hepatic encephalopathy is a chronic disorder that occurs in the setting of alcoholic cirrhosis with portosystemic shunts. There is a wide range of presentations progressing successively through stages: (1) unimpaired cognitive function with intact consciousness; (2) lethargy and confusion/ delirium; (3) somnolence and disorientation; and (4) coma. In the early stages, mood disorders, sleep disturbances, and personality changes can be seen. Asterixis (ie, negative myoclonus, flapping tremor, liver flap) is a typical feature of presomnolent hepatic encephalopathy (01; 02; 03; 04; 258; 198). Various forms of intercurrent illness (eg, infections, gastrointestinal bleeding from esophageal varices, hypoxia, electrolyte disturbances, etc.) and some medications can precipitate abrupt worsening of hepatic encephalopathy.

Several scales have been proposed for assessing or staging hepatic encephalopathy (313). The most commonly used are the West Haven criteria to differentiate between four grades of clinically overt hepatic encephalopathy (310), often augmented by the addition of minimal hepatic encephalopathy (Table 1).

|

Grade |

Manifestations | |

|

Unimpaired |

• No encephalopathy | |

|

Minimal |

• Psychometric or neuropsychological alterations (eg, psychomotor speed, executive function) | |

|

West Haven criteria grade |

I. |

• Trivial lack of awareness |

|

II. |

• Lethargy or apathy | |

|

III. |

• Somnolence to semi-stupor | |

|

IV. |

• Coma | |

Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration. Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration is a disorder of progressive cerebellar degeneration, sometimes seen in patients with severe alcoholism (306). The rate of progression is variable. The anterior and superior vermis are preferentially affected, giving rise to a remarkably stereotypic syndrome of ataxic stance and gait. A wide-based gait and an inability to tandem walk are the most prominent signs. Limb ataxia, if present, occurs primarily in the legs. Arms are involved only to a slight extent, if at all. The gait disturbance usually develops over several weeks. Sometimes, a mild gait instability may be present for some time and then deteriorate suddenly after a bout of binge drinking or an intercurrent illness. The pathogenesis of this disorder is multifactorial and likely includes thiamine deficiency and the toxic effects of alcohol. The disorder predominantly affects middle-aged men (142). In autopsy series of decedents with a history of chronic ethyl alcohol abuse, alcoholic cerebellar degeneration was diagnosed in anywhere from 11% to 27% of cases (289; 320).

Results of brain trauma during alcohol intoxication. Alcoholic patients are prone to traumatic injuries of the brain and the peripheral nerves. Well-recognized central nervous system complications include subdural and epidural hematoma, cerebral contusion, and posttraumatic epilepsy. Compressive neuropathies may appear after a period of prolonged unconsciousness. These may involve the radial nerve at the spiral groove (Saturday night palsy), the peroneal nerve at the fibular head, or the sciatic nerve in the gluteal region.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome. Central pontine myelinolysis/extrapontine myelinolysis (CPM/EPM) and its association with alcoholic and malnourished patients was reported by Adams and colleagues in 1959 (05). They found that rapid changes in electrolyte concentration, most commonly of sodium, are associated with CPM/EPM. Today, these entities are also called the osmotic demyelination syndrome (236). Central pontine myelinolysis is a neurobehavioral disorder associated with rapid onset of quadriparesis, pseudobulbar palsy, pupillary abnormalities, behavioral changes, and sometimes coma (64; 285).

Tobacco-alcohol amblyopia (tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy). Tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy--part of the large group of nutritional and toxic optic neuropathies—is a rare disorder of decreased central vision associated with nutritional deficiencies and tobacco smoking (63; 268). Tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy is characterized by bilateral visual disturbances with grossly diminished visual acuity, papillomacular bundle damage, symmetric scotomas, acquired disturbances of color vision, and mostly normal fundi (251; 156; 89; 25). In a series of 40 cases, central scotomas were present in 80%, whereas centrocecal scotomas (ie, located between the central point of fixation and the blind spot with a roughly horizontal oval shape) prevailed in the rest (156). The acquired disturbances of color vision usually involve the red-green sense (84%) (156). The amplitudes of the visual evoked potentials are typically reduced and deformed (156).

Alcoholic neuropathy. Among the most prevalent neurologic syndromes in alcoholism is a distal, predominantly sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy (26; 55; 190). Tingling or burning pain is often the symptom that brings the patient to medical attention. Dysesthesias are most prominent over the soles and toes and may be severe enough to interfere with walking. As the disease progresses, loss of sensation becomes more pronounced, and neuropathic pain often paradoxically lessens in severity. Neurologic examination reveals abnormally elevated sensory thresholds to vibration, temperature, and pinprick. Distal muscle atrophy and mild weakness are sometimes seen. Ankle tendon reflexes are diminished or absent. Romberg sign, gait disturbances, and more widespread areflexia, weakness, and sensory loss may be seen in advanced cases. Autonomic disturbances (eg, impotence, sweating abnormalities, and orthostatic hypotension) are common, but often overlooked (190; 40). Rare, neuropathic "Charcot" joints may develop from deafferentation, and hoarseness may develop if the neuropathy involves the recurrent laryngeal nerves.

Pressure-induced focal neuropathies can also be linked to the development of myopathy (be considered as a secondary alcoholic neuropathy). The most common is a radial nerve palsy (ie, the so-called “Saturday night palsy” as it typically followed the carousing of a Saturday night) that resulted from radial nerve compression between the humerus and a hard object (eg, the arm of a park bench) during a drunken stupor.

Alcohol-induced (dry) beriberi. Some nutritionally compromised alcoholics may develop a subacute neuropathy due to thiamine deficiency—dry beriberi. Symptoms may evolve over a period of weeks or months. The most common presentation is flaccid weakness and at nadir, many cannot walk independently (194; 49; 121; 249; 67; 279). Other features include numbness/paresthesia, dysautonomia, vocal cord dysfunction, dysphagia, and nystagmus. Some may have concomitant Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (70).

Alcoholic myopathy. Alcohol can produce several myopathic disorders, including acute alcoholic myopathy with or without myoglobinuria, hypokalemic myopathy, chronic atrophic myopathy, and cardiomyopathy (220; 183; 302; 158; 164; 294; 82; 143). Acute alcoholic myopathy (also termed “alcoholic rhabdomyolysis and acute alcoholic necrotizing myopathy”) is an uncommon syndrome of abrupt muscle injury that typically occurs in malnourished chronic alcoholics following a binge or in the first days of alcohol withdrawal; experimental studies have demonstrated that both alcohol and nutritional factors are necessary to produce this syndrome (23; 158; 164). Severity ranges from asymptomatic transient elevation of creatine kinase to frank rhabdomyolysis with myoglobinuria. Although in most instances full recovery occurs within days to weeks, death may occur in the setting of acute renal failure and hyperkalemia. Chronic alcoholic myopathy is a gradually evolving syndrome of proximal weakness, atrophy, and gait disturbance that frequently complicates years of alcohol abuse. Muscle strength correlates with lifetime consumption of ethanol. Recovery occurs if alcohol is avoided, but the timeframe of improvement is weeks to months, in contrast to the rapid recovery typical of acute alcoholic myopathy. Pathogenic mechanisms include impaired gene expression and protein synthesis as well as increased oxidative damage and apoptosis.

Traumatic or pressure-induced rhabdomyolysis resulting from a drunken stupor can also be considered a secondary alcoholic myopathy.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (and fetal alcohol syndrome). Prenatal exposure to high levels of alcohol at critical periods of fetal development can impact neural crest development, disrupting the normal processes of facial and brain development, and potentially inducing birth defects that combine morphological stigmata (eg, facial dysmorphism) with neurologic and neuropsychological deficits (275; 200; 35; 157; 168; 173; 248; 270). The range of facial dysmorphism and neurologic and neuropsychologic disorders is called fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, of which fetal alcohol syndrome is the most severe form. The following table details the different fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

|

Craniofacial dysmorphism | ||

|

• Small head circumference | ||

|

Behavioral problems | ||

|

• Aversion to social/eye contact | ||

|

Cognitive deficits | ||

|

• Mental retardation | ||

|

Neuropathology | ||

|

• Microcephaly | ||

|

| ||

Diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome requires identification of a specific pattern of craniofacial dysmorphology (ie, short palpebral fissures; severe midfacial hypoplasia causing a “flat” midface; long flat or “deficient” philtrum; and a thin, elongated upper lip), but most individuals with behavioral and neurologic sequelae of heavy prenatal ethanol exposure do not exhibit defining facial characteristics (173; 270). Minor dysmorphic features can include ptosis, abnormal ear helices, “railroad track” ears, “hockey stick” palmar creases, and a turned-up nose. Short stature and microcephaly are common and may persist into adulthood. Almost half of affected children have significant learning disabilities, and most others have mild intellectual impairment. Speech delay and hyperactivity are common. Nonspecific mild neurologic deficits may include odor and taste abnormalities, fine motor control deficits, and hearing loss.

Brain malformations related to prenatal exposure to ethanol include microcephaly, agenesis/dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, cerebellar hypoplasia, a smaller hippocampus and basal ganglia, neuronal migration errors, holoprosencephaly, myelomeningocele, optic nerve hypoplasia, and hydrocephalus (242; 129; 180).

Children with fetal alcohol syndrome have a higher incidence of vision problems and eye pathology than normal children, including amblyopia, strabismus, hyperopia, anisometropia, and astigmatism (189; 300; 103). Compared with nonaffected children, children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders showed an amblyopia-like pattern of vision deficit, including deficits in visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereoacuity, in the absence of the optical and oculomotor disruptions of early visual experience that usually precede this condition (300). Evidence from animal models suggests that the deficits in spatial vision may be due to alterations in the functional architecture of the neocortex that occurs following prenatal alcohol exposure (300). Eyelid abnormalities are also more common in children with fetal alcohol syndrome, including blepharophimosis (a congenital anomaly in which the eyelids are underdeveloped such that they cannot open as far as usual and permanently cover part of the eyes), epicanthus (rounded, downward-directed fold of skin covering the caruncular area of the eye), telecanthus (an abnormally increased distance between the medial canthi), and ptosis (189; 103).

Alcohol-related central and peripheral nervous system dysfunction may improve with abstinence from alcohol and correction of malnutrition. The degree of recovery depends on the type of damage as well as the severity and chronicity of the disorder.

Alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol withdrawal is associated with increased cost, longer hospitalizations, and higher risk of medical complications and in-hospital mortality after acute ischemic stroke (06).

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. With early recognition and rapid treatment with intravenous thiamine, Wernicke syndrome may resolve with mild or no sequelae. However, without prompt treatment, many survivors are left with a severe amnesia (Korsakoff syndrome) (147). Among those with longstanding or recurrent encephalopathy, persistent cognitive dysfunction or the Korsakoff syndrome eventually emerges. In addition, untreated patients with Wernicke encephalopathy have a significantly increased risk of death, and most patients who succumb are still drinking at the time of death (41).

The prognosis of Korsakoff syndrome (and more specifically of Korsakoff disease) is generally bleak, and most patients are left with a permanent and devastating memory disorder, even if other neurologic features (eg, nystagmus, ataxia, and neuropathy) may improve markedly or even recover completely (81; 282; 178). Some limited recovery of the amnestic disorder may occur within 1 to 3 months and may continue for up to 1 year or more (282). Only about 20% of patients make a substantial recovery (305). Patients' lack of insight further complicates their behavioral management. Most patients with Korsakoff syndrome require institutionalization in some form because of the profound memory impairment (41). Patients may survive for many years, and their death is typically unrelated to the original neurologic disease. Cognitive test performance of detoxified alcoholic Korsakoff patients remains stable over at least 2 years; neither accelerated cognitive decline nor onset of dementia-like symptoms is observed (91).

Alcoholic pellagra. Alcoholic pellagra has a good prognosis for short-term recovery if promptly recognized and treated, but the issues that led to development of the condition in the first place (ie, severe alcoholism and malnutrition) are associated with significant long-term morbidity and mortality.

Marchiafava-Bignami syndrome. Marchiafava-Bignami syndrome has a high mortality rate, and survivors frequently have significant disability, though limited improvement is possible (119).

Alcoholic cognitive impairment. Perhaps the best prognosis is associated with the milder cognitive changes seen in chronic alcoholics with good nutrition. Several studies have shown that with months and years of abstinence, improvements in visuospatial ability and memory can occur, although older alcoholics are less likely to reach the performance levels of their nonalcoholic age cohort. Partial or complete reversal of the brain shrinkage seen on neuroimaging may also occur.

Alcoholic dementia. With alcohol-related dementias, prognosis varies according to the extent to which permanent brain damage has occurred.

Hepatic encephalopathy. The overall prognosis for recovery is poor in patients with alcoholic hepatic encephalopathy. Mortality is commonly due to sepsis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or raised intracranial pressure (41).

Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration. Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration causes irreversible damage, mostly involving the vermis, but also in other areas of the cerebellum (14).

Osmotic demyelination syndrome. The outcome in osmotic demyelination syndrome (CPM/EPM) is variable, and some cases may be asymptomatic: in an autopsy series of 220 consecutive decedents with chronic liver disease, 21 had CPM that was not clinically evident prior to death (266).

Tobacco-alcohol amblyopia (tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy). The outcome is variable and unpredictable.

Alcoholic neuropathy. In patients with peripheral neuropathy, dysesthesia often persists years after the initial manifestation, even with alcohol cessation. Unfortunately, tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy is often underdiagnosed or only detected at a stage when full vision recovery is not possible (53).

Alcohol-induced (dry) beriberi. The prognosis of alcohol-induced dry beriberi is variable. Some recover promptly with thiamine (49), whereas others, with more advanced disease, may recover slowly and incompletely over a period of months to years (194; 121; 70; 67). Deaths may occur from acute heart failure (Shoshin beriberi) or pulmonary embolism (249).

Alcoholic myopathy. In acute alcoholic myopathy, massive muscle injury triggered by acute alcohol abuse may result in multiple organ failure and death. However, alcoholic rhabdomyolysis generally has a good prognosis if renal failure is avoided or is aggressively treated (15). Muscle has a remarkable capacity to regenerate, and most patients with alcoholic rhabdomyolysis recover full muscle function. Even patients who have had multiple episodes of myoglobinuria may have no lasting skeletal muscle effects. In patients with chronic alcoholic myopathy, improvement also is usual when ethanol is avoided.

Individuals with acute alcoholic muscular syndrome with muscle cramps recover within 2 to 4 weeks if they remain abstinent (221).

A 5-year study of the natural history of chronic alcoholic myopathy showed that only half of the sober patients recovered to normal strength, indicating that chronic alcoholic myopathy is only partially reversible. In some alcoholics even a substantial reduction in alcohol consumption may be as effective as complete abstinence in improving muscle strength or preventing its deterioration (79).

Loss of paraspinal muscle mass is a male gender-specific consequence of cirrhosis that predicts complications and death (78). Loss of paraspinal muscle mass was an independent predictor of the occurrence of bacterial infections, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome (78).

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (and fetal alcohol syndrome). Secondary disabilities (eg, school dropouts, criminal behavior, and substance/alcohol abuse problems) are common in young adults with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (191).

Case 1. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. A 48-year-old man with chronic alcoholism was brought to the emergency room after being found at home in a confused state. He was awake but disoriented. Examination showed a partial right abducens palsy and nystagmus in all directions of gaze. Tendon reflexes were normal in both arms and at both knees but absent at the ankles. Babinski sign was absent bilaterally. He was unable to walk independently and fell easily to either side. Brain CT showed mild atrophy of the cerebellar and cerebral hemispheres. Routine blood studies were notable for a serum sodium of 130 mg/dL. He was treated with intravenous fluids, thiamine, and multivitamins.

Repeat examination 2 weeks later showed an alert and coherent patient; however, he thought the year was 1978 and the president was Ronald Reagan. He could not recall events of the last several days but seemed undisturbed by his difficulties. His eye movements were full, with prominent end-gaze nystagmus. He had normal strength in the limbs. Finger-to-nose testing was performed normally, but there was mild dysmetria with heel-to-shin testing. He walked with a wide-based gait, and tandem gait was impossible. Sensory examination revealed severe impairment of vibratory sensation in the toes, normal joint position sensation, and mild dysesthesias to light touch distal to both ankles. Ankle jerks continued to be absent.

With abstinence from alcohol and resumption of a normal diet, his gait improved slowly over a year. He continued to have significant memory deficits and remained unable to function independently. He also complained of burning and tingling pain in the distal lower extremities and received only partial relief from amitriptyline.

Case 2. Cognitive and behavioral changes accompanied by a history of alcohol abuse. A 76-year-old right-handed man presented with a 4-year history of erratic behavior and memory difficulties. Prior to our evaluation, he had a 15-year history of heavy alcohol abuse that persisted after inpatient rehabilitation and participation in Alcoholics Anonymous. Approximately 1 year prior to examination, he began to have difficulty learning his new area code and dialing phone numbers. Both his drive and interest in life were diminished. Although previously easygoing, he became explosive and irritable, often frightening his wife. Unexpectedly, he converted from a liberal Democrat to a fanatical follower of a right-wing political sect and spent much of his time associating with followers of this group. A few months prior to evaluation, he had been caught having an extramarital affair. There was no history of stroke, head injury, or psychiatric disorder. His medications were nifedipine and enalapril.

On examination, the patient was noted to be bright and alert, but had no insight into his problems and blamed his wife for making the doctor’s appointment. He was irritable, disinhibited, and somewhat explosive. Mini-Mental State Exam score was 23/30. On memory testing, he had a slow acquisition rate and a rapid rate of forgetfulness. Remote memory was good with cues. He interpreted proverbs concretely and made several perseverations when asked to perform frontal executive tasks. He had normal language and perfect naming but impaired word-list generation. There were mild visuospatial difficulties. Cranial nerves II through XII were normal, as were motor bulk, power, and tone. Sensory examination showed severe loss of position and vibration sense distal to the elbows and knees. Reflexes were decreased. Babinski signs were present bilaterally. Gait was normal. MRI scan of the brain showed mild to moderate ventricular dilatation and severe cortical atrophy without acute hemorrhage, midline shift, or focal lesions. SPECT scan demonstrated extensive bilateral frontal hypoperfusion and bilateral temporal hypoperfusion.

The patient’s memory loss was relatively mild but was consistent with early Alzheimer disease. Yet, his disinhibition and profound difficulty on frontal systems tasks, along with a SPECT scan with marked frontal involvement, were atypical for early Alzheimer disease and brought up the possibility of either an alcohol-induced frontal syndrome or a degenerative frontotemporal dementia.

Subsequently, the patient’s course was remarkable for progressive cognitive and behavioral difficulties and unrelenting alcohol consumption. Eventually, he became incontinent and required placement in a nursing home where he died. Autopsy revealed severe frontal and hippocampal atrophy and moderate temporal atrophy in the neocortex. On microscopic examination, moderate numbers of neuritic and diffuse plaques in the neocortex and moderate numbers of plaques in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, primarily on the right, were found. There was a marked loss of neurons in the CA-1 and subiculum of the hippocampus but no neurofibrillary tangles and no Pick bodies. Cerebellar structures were normal. Unfortunately, the mammillary bodies were not available for analysis. The patient’s plaque score was sufficient for a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer disease using CERAD criteria, despite atypical features like the absence of neurofibrillary tangles in the cortex and severe neuron loss in frontal cortex.

In retrospect, this gentleman suffered from a mixed disorder with Alzheimer disease leading to progressive memory loss and dementia. The alcohol abuse seems to have exacerbated the memory disturbance. The profound neuronal loss in the frontal lobes was not consistent with Alzheimer disease and may have been secondary to this patient’s chronic alcoholism (110). Hence, the behavioral deficits exhibited by this gentleman may truly represent the ongoing effects of alcohol abuse.

|

• In alcohol intoxication, ethanol fleetingly and weakly binds or interacts with receptor sites on various proteins in a manner similar to that of inhaled anesthetic agents, and it can also change or stabilize ion channels. | |

|

• Alcohol ingestion impairs cellular and molecular processes causing neurodegenerative change through excitotoxicity, free radical formation, and neuroinflammatory damage. | |

|

• Alcohol dependence is a complex brain disorder brain, and its etiology encompasses a vast array of physiologic, immunologic, genetic, hereditary, social, and behavioral factors. | |

|

|

• Alcohol use disorder is a psychiatric diagnosis comprising both dependence and abuse; over 50% of patients treated for alcohol use disorders carry one or more additional psychiatric disorders. |

|

|

• Tolerance develops with frequent or prolonged alcohol intoxication through both metabolic and functional mechanisms: metabolic tolerance refers to changes in the efficiency or capacity to metabolize ethanol, whereas functional tolerance refers to a lessened response to alcohol independent of the rate of alcohol metabolism. |

|

• In contrast to prior notions that ethanol and other alcohols exerted their effects on the CNS by nonselectively disrupting the lipid bilayers of neurons, modern evidence has demonstrated that ligand-gated ion channels are primarily responsible for mediating the effects of ethanol. | |

|

|

• Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is due to thiamine deficiency. |

|

|

• Korsakoff disease is most commonly associated with chronic alcohol abuse, in which case low dietary intake of thiamine is compounded by alcohol-induced impairments in thiamine absorption and metabolism. |

|

|

• At autopsy, the major gross pathologic changes in Wernicke encephalopathy include petechial hemorrhages, grayish and reddish discoloration, and slight softening of the tissues in structures surrounding the third and fourth ventricles. |

|

|

• The neuropathologic changes in Korsakoff syndrome are identical in distribution and histologic character to those of Wernicke encephalopathy, showing only the more chronic findings of the earlier pathologic processes. |

|

|

• Alcoholic pellagra is caused by a deficiency of either nicotinic acid (ie, niacin/vitamin B3) or tryptophan, usually in combination with a lack of other amino acids and micronutrients. |

|

|

• Chronic alcoholism is a risk factor for liver disease, particularly alcoholic cirrhosis with portosystemic shunting, which can result in hepatic encephalopathy. |

|

|

• Various pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed for hepatic encephalopathy, including those that involve hyperammonemia, neuroinflammation, false neurotransmitters, and increased GABA neurotransmission. |

|

|

• Malnutrition is probably not a significant factor in alcoholic cerebellar degeneration; instead, direct neurotoxicity of ethanol is suspected to be the cause of this disorder. |

|

|

• Acute alcoholic myopathy is caused by severe alcoholic binges, usually in drinkers of long duration; in contrast, chronic alcoholic myopathy is caused by prolonged, consistent alcohol abuse rather than binge drinking. |

Alcohol intoxication. Ethanol fleetingly and weakly binds or interacts with receptor sites on various proteins in a manner similar to that of inhaled anesthetic agents, and it can also change or stabilize ion channels.

Inhibitory GABA and glycine receptor subunits are promising candidate genes associated with alcohol dependence, and these subunits, along with a group of ligand-gated ion channels, may be the target site responsible for acute intoxication. Over time, with chronic intake, various physiologic adaptations occur (113; 292).

Excessive ethanol is toxic to the nervous system (51; 68). Moderate alcohol exposure can induce angiogenesis through induction of vascular endothelial growth factor (101). This may explain the cardiovascular-protective effects of modest alcohol consumption. Ethanol, under experimental conditions, has wide-ranging effects on gene expression (205) and various neuronal constituents, including lipid membranes, receptors for GABA N-methyl-D-aspartate (261; 319) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (323), ion channels, G-proteins (46; 262), and second messengers.

Alcohol ingestion impairs cellular and molecular processes causing neurodegenerative change through excitotoxicity, free radical formation, and neuroinflammatory damage. These neurodegenerative changes may involve membrane proteins, neurotransmitters, ion channels, and signaling pathways (07; 58). Alcohol-induced dysfunction or dysregulation of microglia (which play a major role in immune responses to cerebral insults) may induce or exacerbate neurotoxicity (116).

Thirty ounces of an 86-proof alcoholic beverage contain 2250 calories, or approximately 100% of the daily caloric requirement. These are empty calories, as a typical alcoholic beverage contains a negligible amount of protein, vitamins, and minerals; therefore, serious malnutrition is prevalent in people with alcoholism. On the other hand, adequate diet or even nutritional supplements do not prevent many neurologic complications of alcoholism.

Except for acute alcohol intoxication and alcohol-withdrawal syndrome, neurologic complications of alcoholism are likely due to either nutritional deficiency, a direct toxic effect of ethanol, or secondary effects from prior metabolic derangement or cumulative neurologic trauma acquired during bouts of alcohol intoxication (51; 68).

The majority of ingested ethyl alcohol is oxidized to acetaldehyde in the liver. Acetaldehyde is further metabolized to acetic acid, subsequently forming acetyl coenzyme A. During this process, via the cytosolic oxidative pathway of ethyl alcohol metabolism, NAD is reduced to NADH via alcohol dehydrogenase. NADH, the reduced form of NAD, accumulates in mitochondria, hindering mitochondrial metabolism.

Alcohol dependence. Alcohol dependence is a complex brain disorder brain, and its etiology encompasses a vast array of physiologic, immunologic, genetic, hereditary, social, and behavioral factors. A spectrum of use and abuse exists, and progression to more severe levels does not always occur. Habitual intake can lead to abuse, resulting in conflicts in a person’s work and social environments. Abuse can wax and wane over time. Chronic severe abuse can lead to health, legal, and financial problems. Addiction is the end result.

Alcohol use disorder. Alcohol use disorder is a psychiatric diagnosis comprising both dependence and abuse; over 50% of patients treated for alcohol use disorders carry one or more additional psychiatric disorders (274). Two of the genes most strongly suspected of engendering a decreased risk of abusing alcohol are alcohol dehydrogenase types 2 and 1B (72). Thus far, genome-wide association studies have yielded inconsistent results, reinforcing the genetic complexity of alcohol use disorder. A 2015 meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies reported a heritability of approximately 50% (299).

Alcohol withdrawal. Tolerance develops with frequent or prolonged alcohol intoxication through both metabolic or functional mechanisms; metabolic tolerance refers to changes in the efficiency or capacity to metabolize ethanol, whereas functional tolerance refers to a lessened response to alcohol independent of the rate of alcohol metabolism.

In contrast to the prior notions that ethanol and other alcohols exerted their effects on the CNS by nonselectively disrupting the lipid bilayers of neurons, modern evidence has demonstrated that ligand-gated ion channels are primarily responsible for mediating the effects of ethanol (65).

In particular, gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors occupy a central role in mediating the effects of ethanol on the CNS. GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian CNS; consequently, activation of GABAA receptors by GABA decreases neuronal excitability. Ethanol produces both short- and long-term modulation of GABAA receptors (65). Not only does ethanol enhance inhibitory GABAergic neurotransmission (175), but it also suppresses excitatory glutamate release by inhibiting NMDA receptors (77; 44).

Chronic alcohol ingestion leads to increased release of endogenous opiates, activation of GABAA receptors, up-regulation of NMDA-type glutamate receptors (126; 291), increased dopaminergic transmission, and increased serotonin release. When chronic consumption suddenly ceases, GABAA inhibitory actions are decreased, and NMDA excitatory actions are increased, resulting in increased neurotransmitter excitotoxicity effects that can result in hallucinations, tremor, seizures, delirium, and increased body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure.

In addition to alcohol (ethanol), other positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors include benzodiazepines, barbiturates, meprobamate, methaqualone, zolpidem, and propofol. In particular, the ionotropic GABAA receptor protein complex is also the molecular target of the benzodiazepine class of tranquilizer drugs.

Because they act through similar mechanisms, alcohol (ethanol), benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and other CNS “depressants” can produce cross-tolerance. Withdrawal from these substances can produce similar withdrawal syndromes.

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is due to thiamine deficiency. Korsakoff disease is most commonly associated with chronic alcohol abuse, in which case low dietary intake of thiamine is compounded by alcohol-induced impairments in thiamine absorption and metabolism (272; 255; 324). There may also be a contribution from an age-related vulnerability to diencephalic amnesia produced by thiamine deficiency (226).

At autopsy, the major gross pathologic changes in Wernicke encephalopathy include petechial hemorrhages, grayish and reddish discoloration, and slight softening of the tissues with neuronal loss, gliosis, and vascular damage in structures surrounding the third and fourth ventricles and the cerebral aqueduct (289; 154). This anatomically localized capillary dysfunction is due to thiamine deficiency and is not a direct toxic effect of alcohol (14). Regions most prominently affected are the mammillary bodies, dorsal medial nucleus of the thalamus, periaqueductal region, and the tegmentum of the pons. The encephalopathic component of Wernicke encephalopathy is associated with leakage of capillaries around the third ventricle, whereas the ophthalmoplegia and ataxia are secondary to hemorrhages around the aqueduct of Sylvius in the midbrain and the fourth ventricle in the medulla. Cortical changes are frequently, but not universally, reported and are seen as ventricular enlargement and sulci widening, especially in the frontal lobe (301). These pathological changes may occur rapidly, with the onset of clinically apparent Wernicke encephalopathy, or insidiously, without clinically apparent signs of Wernicke encephalopathy.

The neuropathologic changes in Korsakoff syndrome are identical in distribution and histologic character to those of Wernicke encephalopathy, showing only the more chronic findings of the earlier pathologic processes. Bilateral, symmetrically placed, punctate lesions in the area of the third ventricle, fourth ventricle, and aqueduct are the hallmarks of Korsakoff disease. Lesions in the midbrain and cerebellum are responsible for the neurologic symptoms of the Wernicke stage, whereas lesions in the diencephalon (including the mammillothalamic tract) are critical for the amnesia that characterizes Korsakoff disease (321). The characteristic neuropathology of Korsakoff disease includes neuronal loss, microhemorrhages, and gliosis in the paraventricular and periaqueductal grey matter. Interactions involving the thalamus, mammillary bodies, hippocampus, frontal lobes, and cerebellum are important for new memory formation and executive function; the impairment of these circuits significantly contribute to the cognitive defects found in Korsakoff disease (133; 225). However, the minimal lesion(s) necessary for severe amnesia has not been resolved. The mammillary bodies are affected in approximately 80% of cases; however, shrinkage of the mammillary bodies and frontal lobes is visible on MRI for both Korsakoff disease patients and non-Korsakoff alcoholics (128; 76), even if it tends to be more severe in those with Korsakoff disease. Victor and colleagues suggested that damage to the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus is essential in the causation of memory deficits of Korsakoff disease (305), whereas others have implicated both the mammillary bodies and other thalamic nuclei in the anterior and midline areas, including the preretinal nucleus (179; 39; 108; 296; 147; 155). Neurodegeneration of the anterior thalamic nuclei is apparently a characteristic and specific feature in alcoholics with Korsakoff syndrome (108; 296).

Alcoholic pellagra. Alcoholic pellagra is caused by a deficiency of either nicotinic acid (ie, niacin/vitamin B3) or tryptophan, usually in combination with a lack of other amino acids and micronutrients (256; 301; 159; 161). Inadequate intake of either niacin or tryptophan was historically most common in areas where corn or millet (with a high leucine content) was the primary foodstuff, but endemic pellagra is now rare because cereals and bread are supplemented with niacin. Secondary deficiency may occur due to certain medications, diarrhea, alcoholism, cirrhosis, or some combination of these. Alcoholics with pellagra have a higher prevalence of protein malnutrition than nonpellagrous alcoholics, as reflected in greater frequencies of anemia and hypoalbuminemia and in lower serum potassium levels (61). Depression in pellagrins may be due to a serotonin deficiency caused by decreased tryptophan availability to the brain (19). Alcoholism can induce or aggravate pellagra by: (1) inducing malnutrition, gastrointestinal disturbances, and B vitamin deficiencies; (2) inhibiting the conversion of tryptophan to niacin; and (3) promoting the accumulation of the heme precursor 5-aminolaevulinic acid and porphyrins (137; 19).

Marchiafava-Bignami disease. In Marchiafava-Bignami disease, there is demyelination of the corpus callosum. The pathogenesis of Marchiafava-Bignami disease is unknown, but the underlying pathologic changes in the corpus callosum resemble those of central pontine myelinolysis with selective destruction of white matter; in addition, Marchiafava-Bignami disease has rarely been seen in reported alcohol abstainers, suggesting that other factors (eg, nutritional) may play a role. A link between abuse of red wine and the disorder has been suggested (196).

Alcoholic dementia. Chronic and excessive alcohol use has both direct and indirect effects on central nervous system function. A small study suggested a possible association between reduced brain glucose metabolism and cortical thickness in alcohol use disorder (286). Whether or not the direct effects of alcohol abuse can independently produce a dementia syndrome continues to be debated (174). If an alcohol dementia truly exists, it is often mild enough that the ability to perform activities of daily living is retained. There is a much stronger consensus that indirect effects of alcoholism produce dementia. These indirect etiologies include metabolic thiamine or niacin deficiency. Marchiafava-Bignami disease, which is associated with degeneration of the corpus callosum, is also considered a complication of alcohol, possibly red wine.

The biological bases for alcohol-induced dementia vary. Alcohol quickly crosses the blood-brain barrier, and both alcohol and its major metabolite, acetaldehyde, can be neurotoxic. Prolonged use seems to lead to neuronal loss, neuroglial proliferation, dendritic simplification, and reduction in synaptic complexity. The frontal and parietal lobes may be particularly sensitive to the effects of alcohol, although this is far from proven. Studies using well-nourished animals have shown ethanol-induced reductions in choline acetyltransferase, cell loss in the nucleus basalis, and altered dendritic spines in the hippocampus (50). In humans, these effects are observable on CT and MRI as enlargement of the lateral and third ventricles and mild to moderate sulcal widening. The fact that the atrophy is reversible after sustained periods of abstinence argues that some of these changes are due to shrinkage rather than outright cell death. Cerebellar degeneration, particularly in the region of the anterior and superior vermis, is also commonly seen in chronic alcoholics (288).

Hepatic encephalopathy. Chronic alcoholism is a risk factor for liver disease and particularly alcoholic cirrhosis with portosystemic shunting, which can result in hepatic encephalopathy. Various pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed for hepatic encephalopathy, including those that involve hyperammonemia, neuroinflammation, false neurotransmitters, and increased GABA neurotransmission. Arterial blood ammonia concentrations are typically elevated in hepatic encephalopathy, with fluctuating ammonia levels roughly correlating with the severity of clinical disease, although a small proportion of patients develop symptoms with normal blood ammonia levels. Moreover, measures that act to reduce ammonia levels are helpful in treating hepatic encephalopathy.

There are no gross abnormalities in the brains of patients who die due to hepatic coma. Microscopic examination shows diffuse hyperplasia of Alzheimer type 2 astrocytes of the cerebral cortex and subcortical grey matter structures (eg, basal ganglia, thalamus, dentate nuclei, and brain stem nuclei).

These pathologic cells have a large vacuolated nucleus with chromatin displaced to one side.

Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration. Malnutrition is probably not a significant factor in alcoholic cerebellar degeneration; instead, direct neurotoxicity of ethanol is suspected to be the cause of this disorder. Pathologic changes in alcoholic cortical cerebellar degeneration involve particularly the anterior and superior portions of the cerebellar vermis and hemispheres.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome. Central and extrapontine myelinolysis, disorders of the osmotic demyelination syndrome, are uncommon demyelinating disorders most frequently involving the pons, midbrain, cerebellum, and lateral geniculate body. CPM/EPM is almost always associated with comorbid chronic conditions, including chronic alcoholism, various causes of hypo- and hypernatremia, liver transplantation, lung infections, malignancies, hemodialysis, and central nervous system dysfunction (141). The underlying etiology of these disorders is complex and not yet clearly delineated; however, there is a strong association with osmotic stress, with the most common predisposing factor being hyponatremia in 78% of cases (236; 123; 263). The aquaporin water channels have also been implicated (227).

Neuroimaging most commonly reveals symmetric demyelinating lesions in the base of the pons, midbrain, cerebellum, lateral geniculate nucleus, deep gray nuclei, spinal cord, and cerebral cortex (293). Neuropathologic features include relatively well-preserved cell bodies with demyelinated axons in the pons and occasionally lesions in the striatum, thalamus, cerebellum, and cerebral white matter (50). Rojiani and colleagues described the following types of lesions: spongy (early demyelination), vacuolar (reactive), and hypercellular (240).

Tobacco-alcohol amblyopia (tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy). Tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy typically occurs in nutritionally deficient patients who abuse both tobacco and alcohol (25; 98; 20). The pathogenesis of tobacco-alcohol amblyopia has been controversial but may involve alterations of methionine and S-adenosyl-L-methionine metabolism, with contributions from cyanide in tobacco smoke, vitamin deficiencies (eg, folate, B12, thiamine), and other nutritional deficiencies (63; 99; 100).

Many have subsumed the outdated term tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy under the larger group of nutritional amblyopia (268), and more recently, the improved terms nutritional optic neuropathy (98; 280; 99) or toxic-nutritional optic neuropathy (25; 20). Indeed, some have argued that tobacco-alcohol is a misnomer because the condition is primarily mediated by nutritional deficits and not ethanol toxicity per se (45; 98), even though the same argument could be leveled at other nutritional neurologic disorders resulting from alcohol abuse combined with a nutritionally deficient diet (eg, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and alcoholic pellagra). Identified nutritional defects in patients with tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy include deficiencies of folate (vitamin B9), cobalamin (vitamin B12), and thiamine (vitamin B1) (88; 312; 63; 89). The role of cyanide in tobacco smoke is unclear because serum thiocyanate levels in "tobacco amblyopes" are relatively reduced compared with healthy smokers (87); therefore, if cyanide derived from tobacco smoke is indeed a causative factor in the development of tobacco-alcohol optic neuropathy, the biochemical defect may be a failure of conversion of cyanide to thiocyanate, its chief detoxification product (269; 87).

Although optic neuropathy is generally assumed in such cases, there is little evidence to suggest that the locus of pathology is restricted to the optic nerve. MRI of the optic nerve is typically normal (136), and electrophysiological evidence indicates that some affected people likely have retinal dysfunction involving the macula (25). Moreover, histopathological studies in animal models showed lesions in the retina, optic nerve and tract, and the maculopapillary bundle (238; 268).

Alcoholic neuropathy. The etiology of alcoholic polyneuropathy is unresolved, but the clinical-pathologic similarity to beriberi (neuropathy due to thiamine deficiency) suggests that nutritional factors, and particularly thiamine deficiency, play a role (62; 208).

Alcohol-induced (dry) beriberi. Alcohol-induced dry beriberi is due to thiamine deficiency, resulting from nutritional compromise in an alcoholic patient.

Alcoholic myopathy. Acute alcoholic myopathy is caused by severe alcoholic binges, usually in drinkers of long duration. Chronic alcoholic myopathy is caused by prolonged, consistent alcohol abuse rather than binge drinking. Although myopathy and neuropathy are frequently both present in chronic alcoholics, the pathogenetic mechanisms involved in each of these forms of tissue damage are presumably not identical because histologic and clinical evidence of myopathy may occur in the absence of symptoms or electrophysiologic signs of neuropathy or of malnutrition (183; 294). Nutritional factors may contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic alcoholic myopathy because muscle weakness and histologic myopathy among alcoholics are both more severe in the presence of malnutrition (203).