Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Combined third, fourth, and sixth nerve palsies

Jul. 17, 2024

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Worddefinition

At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti quos dolores et quas.

With subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the takeoff of the vertebral artery, there is a compensatory shunting of blood from the ipsilateral vertebral artery to supply the arm, thus, “stealing” blood from the vertebrobasilar system. In most patients with subclavian steal, the steal is asymptomatic (subclavian steal phenomenon), but a minority may have ischemic symptoms referable to the posterior circulation or the arm. In a minority of cases, neurologic symptoms may be precipitated by ipsilateral arm exercise, head-turning, or standing up. The key signs of a subclavian steal are markedly diminished, delayed, or absent radial pulses on the affected side; supraclavicular systolic bruits; and asymmetric brachial blood pressures, with the lower systolic pressure on the affected side, and generally with a minimum difference of 20 mmHg. Asymptomatic cases should be managed conservatively with vascular risk factor modification and antiplatelet therapy. Endovascular stenting and extrathoracic surgical bypass or transposition (eg, carotid-subclavian) are safe and lasting therapeutic options for selected cases of subclavian steal syndrome, particularly among those with disabling symptoms.

|

• With hemodynamically significant subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the takeoff of the vertebral artery, there is a compensatory shunting of blood from the ipsilateral vertebral artery to supply the arm, thus, “stealing” blood from the vertebrobasilar system. | |

|

• In most patients with subclavian steal, the steal is asymptomatic (ie, subclavian steal phenomenon), but a minority may have ischemic symptoms referable to the posterior circulation or the arm (ie, subclavian steal syndrome). In some cases, neurologic symptoms may be precipitated by ipsilateral arm exercise, head-turning, or standing up. | |

|

• Key signs of a subclavian steal are (1) markedly diminished, delayed, or absent radial pulses on the affected side; (2) supraclavicular systolic bruits; and (3) asymmetric brachial blood pressures, with the lower systolic pressure on the affected side, and generally with a minimum difference of 20 mm Hg. | |

|

• Asymptomatic cases (subclavian steal phenomenon) should be managed conservatively with vascular risk factor modification and antiplatelet therapy. | |

|

• Endovascular stenting and extrathoracic surgical bypass or transposition (eg, carotid-subclavian) are safe and lasting therapeutic options for selected symptomatic cases (subclavian steal syndrome), particularly for those with disabling symptoms. |

Recognition of the phenomenon of subclavian steal dates back to the early 19th century and the insightful observations and deductions of two surgeons (73; 150; 151; 52; 53; 54; 62; 42; 37).

A remarkably astute discussion of vascular collaterals and reversed flow in the vertebral artery with occlusion of the subclavian artery was given by Irish surgeon and anatomist Robert Harrison (1796-1858), Professor of Anatomy and Physiology in the School of Surgery at Trinity College in Dublin:

|

The Student having now concluded the dissection of the arteries of the Neck and superior extremity, may reconsider the various inosculations that exist between these vessels in the different regions of the Neck, Axilla, Arm, fore Arm, and Hand; and he may contemplate the chain of vascular communication extending from the Shoulder to the Fingers, so that if the main artery of the superior extremity be obliterated in any part of its course, he may comprehend those several links by which collateral circulation can be established; for it is well known that in a few hours after the operation of tying the principal artery, the pulse at the Wrist may be distinctly felt. This communication is maintained partly by distinct vessels, which are rendered obvious by dissection; such exist around the Scapula and Elbow, and in the Hand; during life, however, there are numerous inosculations ["To unite parts such as blood vessels, nerve fibers, or ducts by small openings"—in modern parlance "collaterals"] between small arteries from distant sources in the integuments and cellular membrane through the whole of the superior extremity, even on the periosteum and within the bones; these inosculations the Dissector seldom has an opportunity of observing, but they constitute a complete vascular tissue, extending from the Shoulder to the Fingers. Indeed a careful dissection of the arteries of a limb, in which the main trunk has been for some time obliterated, clearly proves, that the anastomosing arteries are derived not from any one particular series of vessels, but that they are supplied by every contiguous ramification. It cannot, however, he uninteresting to the Student to reflect on those particular vessels which constitute the more obvious and direct media of communication, in case obstruction to the flow of blood exists in any part of the artery of the superior extremity. Suppose this obstruction to have occurred in the Subclavian Artery, in the first stage of its course, and before it has given off any branch, the Arm will be then indebted for its principal supply of blood to the following inosculations: — The Vertebral Artery, from its anastomosis with the opposite Vertebral, and with the internal Carotid Arteries, will receive a considerable share of blood, which it will transmit into the Subclavian beyond the obstruction; the inferior Thyroid Artery, from its free communication with the superior Thyroid, will contribute to the same effect (73). |

In 1864, at the suggestion of New York surgeon David L Rogers (1799-1877), American surgeon Andrew Woods Smyth (1833-1916) of New Orleans, then a house surgeon at the Charity Hospital, first successfully ligated the innominate artery for subclavian artery aneurysm (151). To prevent collateral and recurrent blood flow to the aneurysmal sac, Smyth also ligated the right common carotid artery. Then, 2 weeks later, the ligature came away from the carotid, and the patient sustained a major hemorrhage and syncope. Over the ensuing several weeks, recurrent hemorrhages occurred that proved difficult to control. In a later procedure, 57 days after the initial procedure, Smyth ligated the right vertebral artery. Smyth's patient remained alive and functional for 10 years.

|

It was the occurrence of syncope and the consequent arrest of hemorrhage that first directed my attention to the vertebral artery as being the one from which the bleeding took place. This artery is capable of draining the blood directly from the brain, therefore the one most likely to produce these effects, and are petition of hemorrhage had been a striking feature in almost all the cases operated upon. Believing the hemorrhage to come from the distal side of the ligature, and from the subclavian artery, the carotid having been tied, I determined on July 8th to ligature the right vertebral artery, this being the principal branch carrying a retrograde current into the subclavian (Smith 1869). |

Smyth's case was publicized by American physician and physiologist Bennett Dowler (1797-1879), who suggested after the success of the operation became apparent, that the delay between ligating the vertebral after prior ligation of the innominate and carotid arteries contributed to the procedure’s success.

|

The success of your operation was clearly owing to your happy resolution in relation to tying the vertebral artery. But it appears to me in reflecting on your case, that there is coupled with this, another element to be accredited to your success; and that is your having tied it at the time you did, rather than at the time of the first operation (151). |

In 1960, a century after Smyth's successful surgery, Italian surgeon L Contorni described angiographic findings of retrograde flow in the vertebral artery and stenosis of the proximal subclavian artery in a patient with an absent radial pulse but without neurologic symptoms (41; 42). In 1960, neurologist James F Toole (1925-2022) suggested that proximal subclavian artery stenosis or occlusion might cause vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and the following year, Reivich, Holling, Roberts, and Toole reported two patients with evidence of cerebral ischemia and reversal of blood flow through the vertebral artery; they provided experimental results in dogs that confirmed the clinical observations (133; 162; 119; 10; 165; 76). An anonymous editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine designated the syndrome as “the subclavian steal,” and this label served to popularize the condition (11); Canadian neurologist C Miller Fisher (1913-2012) coined the term “the syndrome of the subclavian steal” (63; 119). Toole and colleagues were instrumental in the subsequent elaboration of understanding of various steal syndromes as well as the evaluation and management of affected patients (163; 164; 40; 119; 166; 10; 165). Because steals are often asymptomatic, Vollmar suggested in 1971 that the term “steal syndrome” be reserved for situations in which shunting occurs with symptoms of deficient blood flow, and “steal phenomenon” (or “steal effect”) should be used for asymptomatic steals (173). Vollmer’s suggestion has subsequently been adopted.

Various synonyms for subclavian steal have been used in the past, but none of these older terms gained acceptance, and none are current terminology. These include brachio-basilar insufficiency syndrome, brachio-vertebral syndrome, subclavian suction syndrome, and vertebral grand larceny.

Since the initial description of subclavian steal, various other steal phenomena have been described. Cerebral steal can occur in the setting of focal cerebral ischemia if the patient’s blood pressure drops, if the patient is given a vasodilator, or if the patient is hypoventilated (PaCO2 increases and pH decreases), causing arterioles in nonischemic brain to dilate and, thereby, shunting blood flow from the ischemic areas that require oxygen (56; 165; 06). This has been called the “reversed Robin Hood syndrome” on the basis that it serves to “rob the poor to feed the rich” (06). Intracranial steal phenomena also occur with angiomas and arteriovenous fistulas (105; 139). Similarly, coronary steal (cardiac steal) occurs when a coronary vasodilator is used in the setting of narrowing of the coronary arteries, causing blood to be shunted away from the coronary vessels supplying the ischemic areas and, thereby, causing further ischemia; this phenomenon is used diagnostically in drug-based cardiac stress tests. Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome is a rare but well-recognized complication of coronary artery bypass graft surgery when a left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft is used, and proximal left subclavian artery stenosis is either present or develops subsequently; the result is retrograde flow from the LIMA graft to the distal subclavian artery to perfuse the left arm, causing accentuation of, rather than relief from, cardiac ischemia (43; 127; 86; 170; 44). Vascular access steal (or dialysis-associated steal) refers to vascular shunting resulting from a surgically created arteriovenous fistula or synthetic vascular graft-AV fistula (57; 137; 26; 121; 45; 09; 39; 116; 131; 149; 174); vascular access steal syndrome is associated with pain distal to the fistula as well as pallor, depressed pulses distal to the fistula, necrosis, a decreased wrist-brachial index (below 0.6), and rarely with neurologic manifestations of vertebrobasilar insufficiency (137; 84). Axillo-femoral bypass stead due to subclavian artery stenosis has also been reported (146).

|

• In most patients with subclavian steal, the steal is asymptomatic (subclavian steal phenomenon) and is only discovered incidentally on a carotid and vertebral ultrasound study done for other reasons. | |

|

• It is only when subclavian steal is symptomatic that the term "subclavian steal syndrome" is applied. | |

|

• The most common symptoms of subclavian steal syndrome are referable to the posterior circulation or the arm and include vertigo, nonvertiginous dizziness or lightheadedness, blurred vision, diplopia, syncope, headaches, arm pain (“arm claudiation”), arm fatigue, nausea or vomiting, ataxia, and tinnitus. | |

|

• The key signs of a subclavian steal are: markedly diminished, delayed, or absent radial pulses on the affected side; asymmetric brachial blood pressures, with the lower systolic pressure on the affected side, and generally with a minimum difference of 20 mm Hg; and supraclavicular systolic bruits. |

Subclavian steal results from subclavian artery occlusion or hemodynamically significant stenosis proximal to the origin of the vertebral artery that results in lower pressure in the distal subclavian artery. To compensate, blood is pulled (or stolen) retrograde through the subclavian artery, resulting in "subclavian steal." In most patients with subclavian steal, the steal is asymptomatic and is only discovered incidentally on a carotid and a vertebral ultrasound study done for other reasons. It is only when subclavian steal is symptomatic that the term "subclavian steal syndrome" is applied.

The average age of patients with subclavian steal syndrome is 50 to 60 years, and in cases due to atherosclerosis is generally over age 40 years, but there are also rare congenital cases (119) and uncommon cases due to other causes. Males are affected more commonly than females (119). Roughly 75% to 80% of cases are left-sided, with the left-sided predominance generally attributed to greater turbulence and atherosclerotic development in the more acutely angled left subclavian artery.

The most common symptoms of subclavian steal syndrome are referable to the posterior circulation or the arm (119; 31; 128; 144; 81; 127; 89; 177). These include vertigo, non-vertiginous dizziness or lightheadedness, blurred vision, diplopia, syncope, headaches, arm pain (“arm claudiation”), arm fatigue, nausea or vomiting, ataxia, and tinnitus (119; 148; 31; 81; 127). The syndrome may also cause drop attacks or recurrent transient cochleovestibular dysfunction (eg, vertigo, non-vertiginous dizziness, and subjective tinnitus) (119; 128). Because the vertebrobasilar arterial system supplies both the peripheral and central auditory and vestibular systems, subclavian steal may produce neuro-otological symptoms referable to either central or peripheral structures (128). Visual symptoms and transient paralysis are more common in patients with coincident carotid disease (148).

Symptoms can, in a minority of cases, be precipitated by ipsilateral arm exercise, head-turning, or standing up (119; 31; 81; 177). Although precipitation or aggravation of symptoms with arm exercise has a low sensitivity, it has a high specificity, so the report of neurologic symptoms with or shortly after arm exercise should suggest subclavian steal syndrome.

The key signs of a subclavian steal are the following (119; 158):

|

• markedly diminished, delayed, or absent radial pulses on the affected side | |

|

• asymmetric brachial blood pressures, with the lower systolic pressure on the affected side, and generally with a minimum difference of 20 mm Hg (although some studies suggest a difference of at least 15 mm Hg). The brachial artery pulse may be absent by observation of the arm and present on the opposite side. | |

|

• supraclavicular systolic bruits |

Less common signs include bruises on both knees (patellar sign) in patients with drop attacks. Rarely patients can present with subarachnoid hemorrhage due to dissecting aneurysms of the involved vertebral artery (153).

Asymptomatic cases (subclavian steal phenomenon) have a low rate of causing a stroke (20). When symptomatic (subclavian steal syndrome), though, episodes of vascular insufficiency can involve any brain area irrigated by the vertebrobasilar system, including the upper cervical spinal cord, the brainstem and cerebellum, portions of the posterior thalamus, the occipital lobes, and the medial temporal lobes. The presence of symptoms at presentation is a significant predictor of stroke. In a study of 165 patients with imaging-proven subclavian steal syndrome, approximately one in four developed a stroke with a median follow-up of 28 months (43 of 165 = 26%) (159).

Subclavian steal syndrome causes increased flow through the opposite vertebral artery, and, rarely, this can produce aneurysm formation at the vertebrobasilar junction (161) or even in the spinal cord circulation secondary to collateral formation (70). Such patients can present with subarachnoid hemorrhage (161; 70).

Most patients with coronary-subclavian steal syndrome present with angina pectoris, and secondary myocardial infarction is seldom reported, though it occurs (170).

Complications of vascular access steal (or dialysis-associated steal) include unilateral, episodic, nonthrobbing, nonpostural headaches with transient neurologic symptoms; this pattern of headache may precede overt signs of intracranial hypertension and may be a warning sign of cerebral venous congestion (121).

Case 1: Left subclavian artery stenosis and subclavian steal syndrome (04). A 68-year-old man with multiple vascular risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes) presented with episodic dizziness, presyncope, and visual blurring that occurred with exercise of the left arm. Brachial blood pressures were 150/70 mm Hg on the right and 80/60 mm Hg on the left, with weak left brachial and radial pulses. He had a right anterior cervical bruit and a left supraclavicular thrill and bruit. Conventional angiography revealed severe left subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the origin of the left vertebral artery and associated retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery. The patient underwent left subclavian artery stenting and was also treated with medical therapy, including aspirin, a high-dose statin, and an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor. His symptoms were significantly improved at follow-up 3 months later, at which time the side-to-side difference in brachial systolic pressures had decreased to 15 mm Hg (compared with 70 mm Hg previously), and the left supraclavicular bruit had resolved.

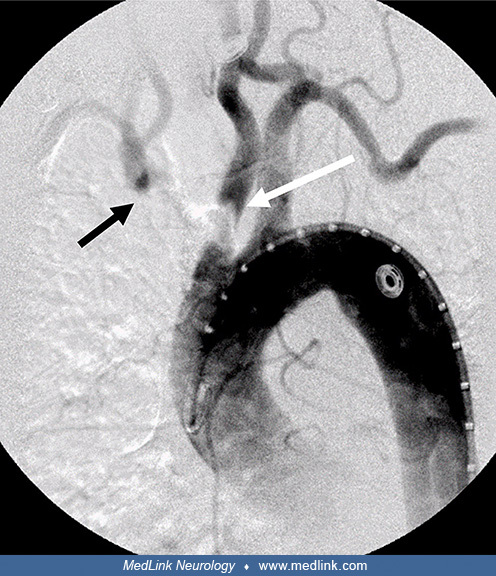

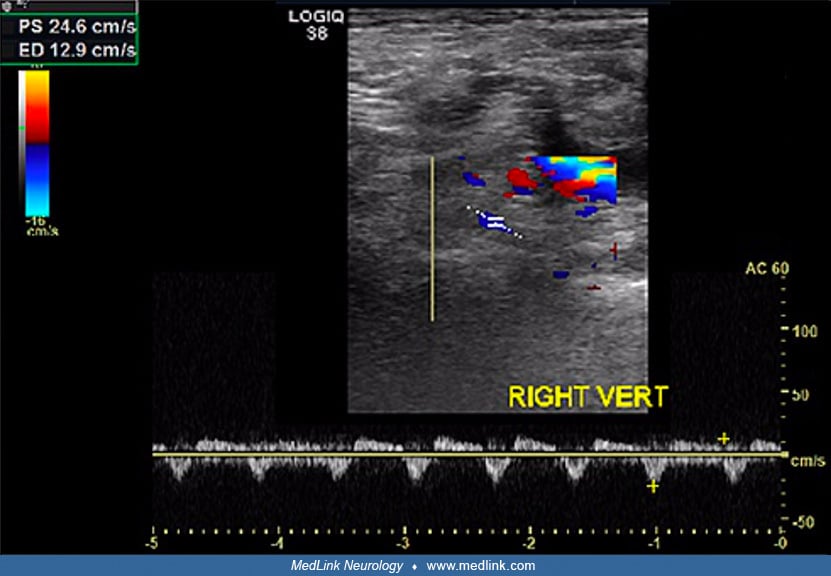

Case 2: Innominate artery occlusion and subclavian steal syndrome (67). A 72-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease with a history of coronary stents, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue presented with increasingly frequent syncopal episodes attributed to vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Carotid duplex imaging demonstrated normal bilateral carotid and left vertebral artery waveform but sustained reversed flow in the right vertebral artery; right transradial angiogram demonstrated innominate occlusion with filling of the right subclavian (black arrow) and the right common carotid (white arrow) arteries.

Carotid duplex imaging shows sustained reversed flow in the right vertebral artery in a 72-year-old woman with innominate artery occlusion and subclavian steal syndrome. (Source: George JM, Cooke PV, Ilonzo N, Tadros RO, Grossi...

Right transradial angiogram in a 72-year-old woman demonstrates innominate occlusion with filling of the right subclavian (black arrow) and the right common carotid (white arrow) arteries. (Source: George JM, Cooke PV, Ilonzo N...

Right transradial angiogram in a 72-year-old woman demonstrates innominate occlusion with filling of the right subclavian (black arrow) and the right common carotid (white arrow) arteries. (Source: George JM, Cooke PV, Ilonzo N...

Arch aortogram revealed innominate artery occlusion with significantly delayed retrograde filling (as well as severe proximal left common carotid artery stenosis).

Arch aortogram in a 72-year-old woman reveals complete occlusion of the innominate artery (black arrow) with delayed filling and severe stenosis of the left common carotid artery (white arrow). (Source: George JM, Cooke PV, Ilo...

The patient underwent a left common carotid to right common carotid artery bypass with stenting of the ostial left common carotid artery lesion. After stent placement, the angiogram demonstrated resolution of the stenosis.

Carotid angiogram after stenting in a 72-year-old woman with innominate artery occlusion and subclavian steal syndrome demonstrates resolution of the left carotid stenosis. The sheath is within the left common carotid artery in...

She was discharged home on dual antiplatelet therapy. Postoperative duplex at one-month and 6-month postprocedure showed a patent carotid artery bypass graft and oscillation of flow in the right vertebral artery.

Postoperative follow-up duplex imaging shows a patent left carotid to right carotid artery bypass graft in a 72-year-old woman with innominate artery occlusion and subclavian steal syndrome. (Source: George JM, Cooke PV, Ilonzo...

Postoperative follow-up duplex imaging of the right vertebral artery shows oscillation of flow after bypass with stenting in a 72-year-old woman with innominate artery occlusion and subclavian steal syndrome. (Source: George JM...

Case 3: right subclavian artery stenosis and subclavian steal syndrome (12). A 43-year-old man was evaluated for repeated transient ischemic attacks in the vertebrobasilar territory. Duplex ultrasound examination of the cervical vessels revealed a hypoechoic atherosclerotic plaque at the origin of the right subclavian artery, causing severe stenosis (12) and subclavian steal.

A cuff test on the affected side alters blood flow in the ipsilateral vertebral artery during compression above systolic blood pressure in the left arm, and when the cuff is released, the reactive hyperemia of the arm draws greater retrograde flow through the ipsilateral vertebral artery, transiently converting partial retrograde flow at rest to complete retrograde flow.

Color-flow imaging (triplex ultrasound) of the right vertebral artery during compression of the right arm with a blood pressure cuff (a "cuff test") shows the appearance of a minimal positive diastolic flow in a 43-year-old man...

After balloon angioplasty, the subclavian stenosis was significantly reduced, and the subclavian steal disappeared.

Color-flow imaging (triplex ultrasound) ultrasound examination after balloon angioplasty of the right subclavian artery shows a normal triphasic subclavian waveform.

Abbreviations: RSCA=right subclavian artery.

Color-flow imaging (triplex ultrasound) ultrasound examination after balloon angioplasty of the right subclavian artery shows normal, antegrade flow in the right vertebral artery.

Abbreviations: RVA=right vertebra...

|

• Subclavian steal (flow reversal in the vertebral artery) is caused by subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the takeoff of the vertebral artery; the result is a compensatory collateral flow in which there is shunting of blood from the vertebral artery to supply the arm. | |

|

• With subclavian artery steno-occlusive disease, blood is usually supplied to the ipsilateral vertebral artery from a commensurate increase in antegrade flow in the contralateral vertebral artery, or as it has been expressed, “siphoning from the opposite vertebral artery is the most common situation.” | |

|

• With innominate (brachiocephalic) artery steno-occlusive disease, flow may be “stolen” through the vertebral artery and also, at times, through the internal and common carotid arteries. | |

|

• If flow is antegrade in the right common carotid artery, despite brachiocephalic artery occlusion, flow will necessarily be reversed in the proximal subclavian artery (because flow will have to originate from retrograde flow through the takeoff of the more distally placed vertebral artery), whereas if flow is retrograde in the right common carotid artery, flow will be antegrade in the proximal subclavian artery. | |

|

• Supplementary collateral routes are often present, usually connecting the external carotid artery to the distal subclavian artery. | |

|

• Symptoms due to arm ischemia can be spontaneous or may be provoked when increased flow needs (eg, with exercise) cannot be met through the stenotic or occluded subclavian artery in combination with reversed flow in the vertebral artery and with whatever other minor collateral pathways are invoked. | |

|

• Whether subclavian steal causes cerebral ischemic symptoms depends on the adequacy of the intracranial collateral circulation, but in general, neurologic symptoms are relatively infrequent with subclavian steal. | |

|

• By far, the most common cause of subclavian steal is atherosclerosis. |

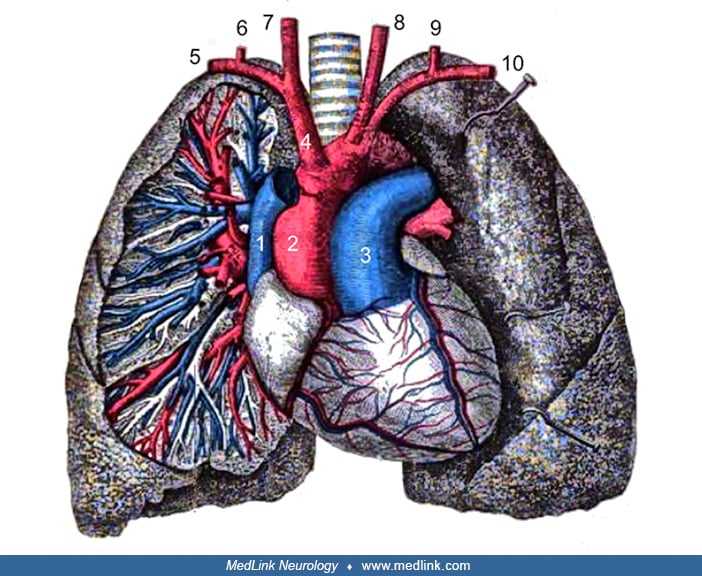

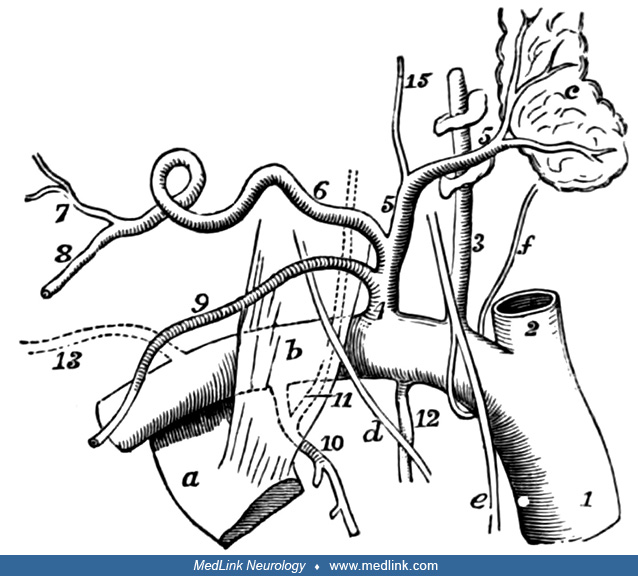

Under the prototypical vascular arrangement, there are three major branches of the aortic arch: the innominate (brachiocephalic) artery, the left common carotid artery, and the left subclavian artery.

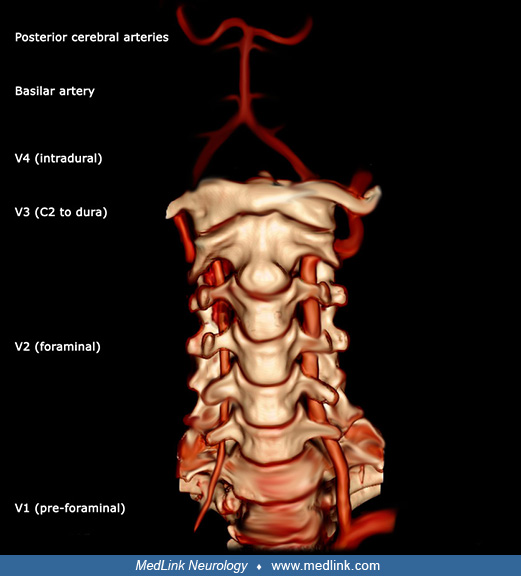

The innominate artery bifurcates into the right subclavian and right common carotid arteries. The first branch of the subclavian artery is the vertebral artery, which has a pre-foraminal portion (V1), then ascends through foramina in the transverse processes of C6 through C2 (V2), proceeds to the dura (V3), and then extends to its confluence with the opposite vertebral artery (V4) to form the basilar artery.

The basilar artery bifurcates in the posterior cerebral arteries, which connect to the anterior circulation in the posterior communicating artery. The anterior terminus of the posterior communicating artery is the internal carotid artery before the terminal bifurcation of the internal carotid artery into the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. Other branches of the proximal subclavian artery include the internal mammary (internal thoracic) artery and the thyrocervical trunk (which divides into the inferior thyroid artery, the suprascapular artery, and the transverse cervical artery [cervicodorsal trunk]).

With innominate or subclavian artery steno-occlusive disease, subclavian artery branches distal to the obstruction act as collateral pathways to maintain upper limb perfusion. The vertebral loop from one subclavian artery up the corresponding vertebral artery to the confluence of the vertebral arteries (where the basilar artery is formed) and down the opposite vertebral artery to the opposite subclavian artery is an important collateral pathway in patients with steno-occlusive disease of the innominate or subclavian arteries.

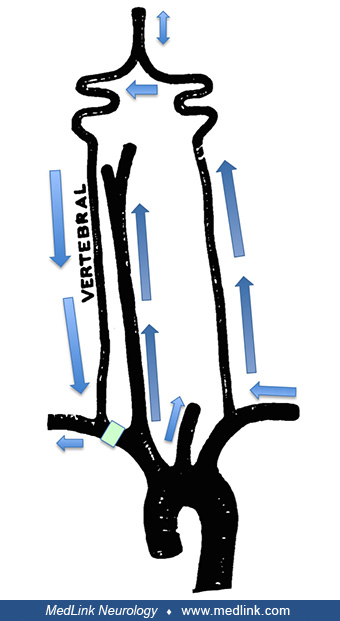

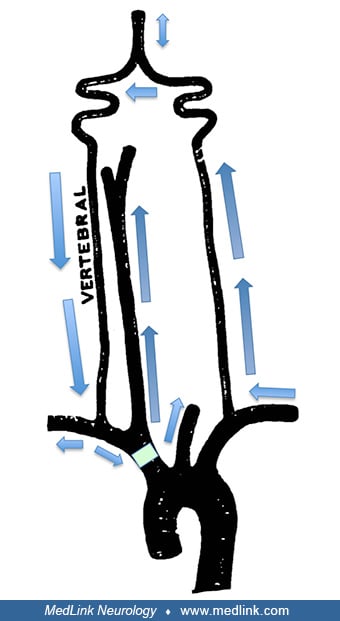

Subclavian steal (flow reversal in the vertebral artery) is caused by subclavian artery stenosis proximal to the takeoff of the vertebral artery.

The result is a compensatory collateral flow in which blood is shunted from the vertebral artery to supply the arm. In its mildest form, flow remains antegrade in the vertebral artery, but much of the systolic flow is shunted to the arm. Further progression produces bidirectional flow, typically with antegrade flow in early systole and retrograde flow in late systole, and then ultimately fully reversed flow.

With subclavian artery steno-occlusive disease, blood is usually supplied to the ipsilateral vertebral artery from a commensurate increase in antegrade flow in the contralateral vertebral artery, or as it has been expressed, “siphoning from the opposite vertebral artery is the most common situation” (119).

Intermittent or complete flow reversal in the basilar artery can occur with unilateral steno-occlusive disease of the subclavian artery (109; 119; 88; 186; 47; 72) but is uncommon even with complete subclavian steal (21; 75; 47; 72; 13). Intermittent or complete flow reversal in the basilar artery is more likely with symptomatic unilateral subclavian steal with defined vertebrobasilar symptoms (47) or with unilateral subclavian steal with significant contralateral or ipsilateral vertebral artery steno-occlusive disease (117; 102; 47).

With innominate (brachiocephalic) artery steno-occlusive disease, flow may be “stolen” through the vertebral artery and also at times through the internal and common carotid arteries (147); if flow is antegrade in the right common carotid artery, despite brachiocephalic artery occlusion, flow will necessarily be reversed in the proximal subclavian artery (because flow will have to originate from retrograde flow through the takeoff of the more distally placed vertebral artery), whereas if flow is retrograde in the right common carotid artery, flow will be antegrade in the proximal subclavian artery (119).

When there is stenosis of both subclavian arteries, or of both the innominate (brachiocephalic) and left subclavian arteries, or when there is steno-occlusive disease affecting the vertebral or carotid arteries, a variety of alternate collateral pathways may be invoked (102; 147). With bilateral subclavian steal, flow is most commonly supplied by reversed flow in both vertebral arteries and, hence, reversed flow in the basilar artery, which, in turn, is supplied through the posterior communicating arteries (109; 119).

Consequently, vertebrobasilar insufficiency is several times more common with bilateral than with unilateral subclavian steal (69).

Supplementary collateral routes are often present, usually connecting the external carotid artery to the distal subclavian artery (eg, mediated through anastomoses between the occipital artery and the cervical branches of the costocervical and thyrocervical trunks or through anastomoses between the superior and inferior thyroid arteries) (92; 89).

Symptoms due to arm ischemia can be spontaneous or may be provoked when increased flow needs cannot be met through the stenotic or occluded subclavian artery in combination with reversed flow in the vertebral artery and with whatever other minor collateral pathways are invoked. This may occur, for example, with arm exercise or with postischemic hyperemia when a cuff test is performed or if reversed vertebral flow is limited in the intertransverse segment with turning or extending the head.

Whether subclavian steal causes cerebral ischemic symptoms depends on the adequacy of the intracranial collateral circulation. In fact, neurologic symptoms are relatively infrequent with subclavian steal. Computational modeling of blood flow steal phenomena caused by subclavian stenoses suggested that regional brain steal occurs, primarily affecting the posterior circulation that is not fully compensated by the anterior circulation (18). Indeed, neurologic symptoms usually occur when steno-occlusive disease affects other areas of the cerebral circulation and compensatory mechanisms are unable to supply the flow needed, resulting in ischemic symptoms referable to vertebrobasilar or carotid territories (92). Such symptoms (often vertebrobasilar insufficiency) may also resolve spontaneously as further collaterals are developed to supply the subclavian circulation.

By far, the most common cause of subclavian steal is atherosclerosis, but additional uncommon causes have been recognized since the original descriptions of subclavian steal in the 1960s. Less common causes include giant cell arteritis and especially the subtype of Takayasu's arteritis (103; 134; 185; 50; 168; 120; 183), congenital malformations of the aortic arch and great vessels (24; 68; 93; 97; 172; 14; 123; 142; 155; 23; 124; 16; 101; 66; 29; 91; 156; 176; 82; 94; 122; 182; 60; 58; 46; 38; 96), iatrogenic causes related to surgical procedures (eg, with failed shunt placement, surgery for coarctation of the aorta, hemodialysis shunt, etc.) (101; 141; 78; 114; 79; 08; 51; 65; 137; 26), prior head and neck radiation therapy (177), and aneurysmal expansion of the subclavian artery (115; 28).

Giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis are the same entity with different phenotypes (98). Takayasu arteritis is a rare form of large-vessel, chronic, occlusive vasculitis of unknown origin that mainly involves the aorta and its main branches, causing stenosis, obstruction, or aneurysmal dilation. According to the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitis (1994), it is a "granulomatous inflammation of the aorta and its major branches" by (80). It occurs principally in young women of childbearing age (age 15 to 40 years) and is more prevalent in Asia and Latin America. Depending on the vascular territories involved, it may cause subclavian steal syndrome as well as angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, and renovascular hypertension (103; 134; 185; 50; 120; 168; 183). Cases of subclavian steal syndrome have also been reported with temporal arteritis (126; 132; 111; 112; 130).

Aortic dissections may rarely cause subclavian steal and related steal phenomena (100; 22; 59). In cases of aortic dissection extending to the innominate and right common carotid arteries, cases have been reported in which the right subclavian artery is supplied by retrograde flow from the right common or internal carotid artery through the false lumen of the dissection (22; 59).

Congenital subclavian steal rarely occurs as a result of anomalies in the development of the aortic arch and great vessels (101; 94; 46). With normal development, the primitive aorta consists of ventral and dorsal parts, which are continuous through the first aortic arch.

The dorsal aortae initially form separately on either side of the notochord, but by the third week, they fuse to form a single trunk, the descending aorta. Six pairs of aortic arches are formed. The first and second arches pass between the ventral and dorsal aortae, whereas the others arise at first by a common trunk from the truncus arteriosus but end separately in the dorsal aortae. As the neck elongates, the ventral aortae are drawn out, and the third and fourth arches arise directly from these vessels. In mammals, some of them remain as permanent structures, whereas others disappear or become obliterated.

The most common circumstance resulting in congenital subclavian steal is an anomalous right-sided aortic arch associated with a left-sided subclavian steal by ”isolation” of the left subclavian artery from the aorta; the left subclavian artery is instead connected to the left pulmonary artery by a left ductus arteriosus (a malformation that often occurs in association with other congenital cardiac anomalies, especially tetralogy of Fallot) (94; 99).

About a quarter of such patients are symptomatic with either vertebrobasilar symptoms or left arm weakness (94; 46).

Isolation of the left brachiocephalic artery has been classified into three types based on the presence or absence of a connection of the left brachiocephalic artery to the pulmonary artery and the number of sources of steal from the left brachiocephalic artery (99): (1) a single-steal type, with no connection of the left brachiocephalic artery to the pulmonary artery and a single source of steal from the left brachiocephalic artery through the left subclavian artery; (2) a double-steal type, with connection of the left brachiocephalic artery to the pulmonary artery through a patent arterial duct (also known as persistent ductus arteriosus or patent ductus arteriosus) and two sources of steal through the left subclavian artery and the arterial duct; and (3) a triple-steal type, with bilateral persistent arterial ducts and, consequently, three routes of steal from the left brachiocephalic artery (ie, the left subclavian artery and the double patent arterial ducts). Patients with the single-steal type have the best prognosis and present latest with symptoms of cerebrovascular insufficiency or left arm claudication (99). The double-steal type is the most common type and is often associated with genetic syndromes and extracardiac anomalies. The triple-steal type is the rarest type and has the earliest presentation and the worst prognosis. All reported cases have had cardiac symptoms, pulmonary overcirculation, pulmonary hypertension, and a fatal outcome (99).

With a left-sided aortic arch, congenital subclavian steal can rarely occur with proximal atresia of either subclavian artery (46). For example, in one reported case, the origin of the right subclavian artery was atretic and was supplied by retrograde flow through the right vertebral artery as well as collaterals near the origin of the internal mammary artery (46). In addition, several variants of subclavian steal can occur as a result of atherosclerotic development superimposed on various anomalies of the aortic arch and great vessels (169).

The incidence and prevalence of subclavian steal and subclavian steal syndrome have not been defined in population-based groups. In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, 307 participants from among 6743 subjects studied (4.6%) had a systolic blood pressure difference between the right and left brachial arteries of at least 15 mm Hg, which in this study was taken as an indicator of subclavian stenosis, but subclavian steal was not documented (02). Another study estimated that significant subclavian stenosis is present in approximately 2% of the free-living population (based on two cohorts) and 7% of the clinical population (based on two additional cohorts) (143). Subclavian stenosis is positively associated with present and past smoking, systolic hypertension, and the presence of peripheral arterial disease and is negatively associated with HDL levels (143). The presence of subclavian stenosis with or without steal is a predictor of total and cardiovascular mortality, independent of both traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors and established cardiovascular disease at baseline (01).

Subclavian steal is a common incidental finding in patients undergoing carotid ultrasound studies (90). In one study of nearly 8000 carotid duplex scans, a systolic pressure difference of more than 20 mm Hg in the two arms was identified in 514 (6.5%) of the patients studied; of these, there was complete steal (reversed vertebral artery flow) in 61%, partial steal in 23%, and no steal in 16%. Thus, partial or complete subclavian steal was present in about 5.5% of the patients undergoing carotid ultrasound studies. Symptoms were present in only 38 of these patients (about 9% of those with subclavian steal), with 32 experiencing symptoms referable to the posterior circulation, four experiencing arm ischemia, and two cardiac ischemia. Symptoms were more frequent in those with a higher difference in brachial systolic blood pressure. Only seven patients underwent intervention, two with subclavian-carotid bypass and five with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting of the subclavian artery.

|

• No prevention is available for subclavian steal syndrome. | |

|

• Because subclavian steal phenomenon is a risk marker for vascular disease, risk factor modification is appropriate to prevent adverse vascular outcomes (eg, myocardial infarction and stroke). |

No prevention is available for subclavian steal syndrome, except possibly for iatrogenic surgical cases. However, because subclavian steal phenomenon is a risk marker for vascular disease, risk factor modification is appropriate to prevent adverse vascular outcomes (eg, myocardial infarction and stroke), even if these outcomes result from mechanisms other than subclavian steal.

Retrograde flow in the vertebral artery is synonymous with subclavian steal, but biphasic vertebral flow is not universally due to subclavian steal (35; 34; 74). Biphasic flow (“intermittent completely reversed flow”) may be caused by a hypoplastic vertebral artery and by occlusion of the proximal vertebral artery (35; 34; 74).

Subclavian steal phenomenon is most commonly caused by atherosclerotic disease of the proximal subclavian or innominate artieries, but it can also be caused by giant cell arteritis, trauma, and, rarely, aortic dissection or congenital anomalies. Congenital anomalies should be considered in children and young adults. In women of childbearing years, especially of Latin or Asian origin, Takayasu arteritis should be considered. In elderly patients, temporal arteritis should be considered.

|

• Subclavian steal is most often identified incidentally by ultrasonography as part of a “carotid” duplex study. | |

|

• The degree of subclavian artery stenosis or occlusion may be reflected in the vertebral artery waveform and in specific characteristics of that waveform. | |

|

• In patients with less than complete steal, an upper limb reactive hyperemia test (“cuff test”) can be utilized to assess physiologically the sensitivity of steal phenomena to blood flow needs of the arm, particularly in those with either an early systolic deceleration pattern (“vertebral bunny waveform”) or biphasic flow pattern in one or both of the vertebral arteries on spectral Doppler imaging. | |

|

• Doppler examination of the vertebral artery, including an upper limb hyperemic test (cuff test), has been used to classify patients into three stages: stage 1 (“presubclavian steal”); stage 2 (“intermittent subclavian steal”); and stage 3 (“permanent subclavian steal”). | |

|

• When it may impact clinical outcome (typically in symptomatic cases), further vascular imaging with magnetic resonance angiography, CT angiography, or conventional angiography can be considered. |

Subclavian steal is most often identified incidentally by ultrasonography as part of a “carotid” duplex study (which routinely includes assessment of the V2 segment of the vertebral arteries). Complete flow reversal in a vertebral artery is usually readily detected, but many of those who interpret such studies are less familiar with the spectral Doppler characteristics of partial steal phenomena, which are consequently less often recognized. Furthermore, subclavian artery ultrasound is not often included as part of such studies, even in the face of abnormal flow in a vertebral artery; and in any case, the proximal subclavian artery is not easily insonated because of overlying skeletal structures. The distal subclavian artery and brachial artery may show either a parvus-tardus waveform (prolonged systolic acceleration time with decreased peak systolic velocity, ie, weak or small [parvus], and late [tardus] relative to its usually expected character) or a monophasic waveform (instead of the normal triphasic waveform).

Different stages of subclavian steal on duplex sonography correlate with the degree of subclavian or innominate (brachicephalic) artery stenosis (125; 135; 184; 129; 87; 48; 33). The degree of subclavian artery stenosis or occlusion may be reflected in the vertebral artery waveform and in specific characteristics of that waveform, including both the depth of the midsystolic notch and the peak reversed velocity of the vertebral artery (33). A normal vertebral artery spectral Doppler waveform shows antegrade flow in both systole and diastole, with a unimodal (clearly convex) systolic waveform. The earliest manifestations of subclavian steal on vertebral spectral Doppler waveforms is the “early systolic deceleration” pattern (“vertebral bunny waveform”) (125; 135; 87; 48).

With this pattern, flow in the vertebral artery remains antegrade throughout systole and diastole, but part of the systolic flow is shunted to the distal subclavian artery, producing a characteristic concavity after an initial short systolic spike and a bimodal systolic waveform. The resulting appearance of the waveform envelope is of a rabbit in the grass (48). Most cases with early systolic deceleration have proximal subclavian artery stenosis rather than occlusion. A biphasic (alternating flow) pattern and a fully retrograde flow pattern are generally seen with more severe proximal subclavian steno-occlusive disease, and in particular, a complete vertebral steal correlates well with proximal subclavian occlusion (125; 135; 184; 129; 87).

The degree of compensatory flow velocity increase in the contralateral vertebral artery also correlates well with the severity of subclavian steal (157).

In patients with less than complete steal, an upper limb reactive hyperemia test (“cuff test”) can be utilized to assess physiologically the sensitivity of steal phenomena to blood flow needs of the arm, particularly in those with either an early systolic deceleration pattern (“vertebral bunny waveform”) or biphasic flow pattern in one or both of the vertebral arteries on spectral Doppler imaging (25; 167; 77; 87; 48; 113). The cuff test typically involves inflation of a blood pressure cuff on the suspected side of partial or occult subclavian steal to a level of at least 20 mm Hg over the systolic blood pressure for several minutes. This is done with spectral Doppler ultrasound monitoring of the ipsilateral vertebral artery (and in some cases with monitoring of blood flow in the basilar and middle cerebral arteries using transcranial Doppler ultrasonography). Rapid deflation of the cuff (best done with a trigger release) results in accentuated flow to the post-ischemic arm (reactive hyperemia) and, consequently, an increase in an incipient or partial steal. Even when such a steal is made manifest using this technique, previously asymptomatic patients rarely develop even transient neurologic symptoms. If a patient develops neurologic symptoms after cuff release, the patient should be placed in a fully supine or Trendelenberg position, and the cuff should be immediately re-inflated and then very slowly released.

Another approach to accentuating steal is arm exercise with concomitant or sequential vertebral artery monitoring (133; 136; 119; 165; 95; 175). Because this requires greater patient activity and cooperation, and because monitoring is more difficult with this approach, a “cuff test” is often preferentially used instead.

Doppler examination of the vertebral artery, including an upper limb hyperemic test (cuff test), has been used to classify patients into three stages: stage 1 ("pre-subclavian steal") is characterized by a sudden decrease in the systolic vertebral flow (so-called “early systolic deceleration”) with complete interruption during reactive hyperemia; stage 2 ("intermittent subclavian steal") is characterized by transient reversed vertebral flow during systole with sustained reversed flow for 1 or 2 minutes after arm ischemia; and stage 3 ("permanent subclavian steal") is characterized by complete reversed vertebral flow without diastolic flow and increase of reversed flow during reactive hyperemia (25).

Transcranial color Doppler ultrasound enables examination of the basilar artery and arteries of the circle of Willis (21; 88; 186; 47; 17; 72). Intermittent or complete flow reversal in the basilar artery can occur (88; 47; 72; 186) but is uncommon even with complete subclavian steal (109; 119; 21; 75; 47; 72). It is more likely with bilateral subclavian steal (109), with symptomatic unilateral subclavian steal with defined vertebrobasilar symptoms (47), or with unilateral subclavian steal with significant contralateral vertebral artery steno-occlusive disease (47). Reports are inconsistent whether a cuff test will change basilar artery peak systolic velocity or direction of flow, with some reporting a significant change in basilar artery flow in a subgroup of patients (186; 47) whereas others found no such changes (72). Transcranial Doppler may detect transient retrograde basilar artery flow that is missed by angiography (160).

Chest CT with contrast may show evidence of subclavian artery stenosis, such as subclavian artery plaque and absence of contrast in a vertebral artery suggesting flow reversal.

Chest CT with subclavian artery plaque (red circle) and no contrast in left vertebral artery suggests reversal of flow. (Courtesy of Jason Robert Young MD. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International [CC BY 4.0] license, cre...

When it may impact clinical outcome (typically in symptomatic cases), further vascular imaging with magnetic resonance angiography, CT angiography, or conventional angiography can be considered (184; 64; 30; 171; 145; 179; 13; 138; 127).

CT reconstruction shows almost complete occlusion at the origin of the subclavian artery in an 82-year-old man with left subclavian artery stenosis and subclavian steal phenomenon. (Source: Amano Y, Watari T. "Asymptomatic" sub...

With improved technical developments, magnetic resonance angiography can accurately demonstrate proximal subclavian artery steno-occlusive disease, can often determine the direction of vertebral artery flow (particularly with complete flow reversal), and can identify concomitant steno-occlusive disease in the carotid system and circle of Willis, while avoiding use of iodinated contrast and large x-ray doses, but magnetic resonance angiography is, nevertheless, often limited by claustrophobia, patient movement, and contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging (eg, pacemakers) (64; 30; 171; 179; 13; 138). Unfortunately, some of the technical requirements for such specialized studies are not universally available.

|

• Patients with known subclavian artery stenosis should have blood pressures measured from the nonstenotic side for hypertension-monitoring purposes. This is often overlooked, leading to under-recognition of significant hypertension and, at times, oscillating upward and downward titration of blood pressure medications, depending on which side was used for blood pressure measurement. | |

|

• Subclavian artery steno-occlusive disease is only occasionally associated with symptoms and is often considered a “benign” condition. | |

|

• Asymptomatic cases (subclavian steal phenomenon) have a relatively low rate of developing a stroke and should be managed conservatively with vascular risk factor modification and antiplatelet therapy. | |

|

• Because patients with subclavian steal are more likely to experience a transient ischemic attack or stroke involving the carotid circulation than the vertebrobasilar circulation, noninvasive evaluation of the carotid arteries and the posterior circulation is recommended in the evaluation of such patients. | |

|

• When symptomatic (subclavian steal syndrome), coincident significant carotid system stenoses should be excluded. Symptomatic cases (subclavian steal syndrome) may benefit from surgery. | |

|

• Endovascular stenting and extrathoracic surgical bypass (carotid-subclavian or axilloaxillary) or transposition (carotid-subclavian) are safe, effective, and lasting therapeutic options for selected cases of subclavian steal syndrome, particularly among those with disabling symptoms. |

Patients with known subclavian artery stenosis should have their blood pressure measured from the nonstenotic side for hypertension-monitoring purposes. This is often overlooked, leading to under-recognition of significant hypertension (27) and, at times, oscillating upward and downward titration of blood pressure medications, depending on which side was used for blood pressure measurement. If possible, a separate warning should be added to the problem list so nurses from different clinical services will be alerted to this issue, eg, “Warning: measure blood pressures ONLY on the [list side opposite the subclavian stenosis] side”.

Subclavian artery steno-occlusive disease is only occasionally associated with symptoms and is often considered a “benign” condition (20; 03; 21; 75; 83; 81). Asymptomatic cases (subclavian steal phenomenon) have a relatively low rate of developing a stroke (20) and should be managed conservatively with vascular risk factor modification and antiplatelet therapy. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency is three times more common in bilateral than unilateral subclavian steal (69). Neurologic symptoms are also more common with coincident carotid obstructions or abnormal flow velocity patterns in the basilar artery (75). Patients with subclavian steal are more likely to experience a transient ischemic attack or stroke involving the carotid circulation than the vertebrobasilar circulation (104); consequently, noninvasive evaluation of the carotid arteries and the posterior circulation is recommended in the evaluation of such patients (104). Regardless of neurologic symptoms, the presence of subclavian stenosis with or without steal is a predictor of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events and of both total mortality and cardiovascular mortality, independent of both traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors and established cardiovascular disease at baseline (01; 127).

When symptomatic (ie, subclavian steal syndrome), coincident significant carotid system stenoses should be excluded. Symptomatic cases may benefit from surgery. Endovascular stenting and extrathoracic surgical bypass (carotid-subclavian or axilloaxillary) or transposition (carotid-subclavian) are safe, effective, and lasting therapeutic options for selected cases of subclavian steal syndrome, particularly among those with disabling symptoms (19; 108; 106; 61; 49; 148; 71; 154; 118; 152; 55; 107; 140; 178; 05; 15; 181).

Angiogram of the aortic arch shows plaque in the left subclavian artery (red circle) with decreased blood flow distally (purple arrow) and no contrast extending into the left vertebral artery. (Courtesy of Jason Robert Young MD...

Left subclavian artery stent placed (green circle) with improved distal blood flow (red arrow) and contrast extending into the left vertebral artery (green arrow). (Courtesy of Jason Robert Young MD. Creative Commons Attributio...

In one study of percutaneous endovascular therapy for symptomatic chronic total occlusion of the left subclavian artery, the patency rate among 15 patients at 2 years was 93% (05). These procedures are generally well tolerated, but a number of complications have been reported, including upper extremity thromboembolism and stroke (180; 55). Predictors of in-stent restenosis after subclavian artery stenting include tobacco smoking in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a vessel size of 7 mm or less, stents longer than 40 mm, and possibly younger age at the time of the procedure (107; 85). Stunting is significantly superior to angioplasty alone (32). Cases with visual symptoms or transient paralysis frequently have coexistent carotid disease and may benefit instead from carotid endarterectomy (148).

Endovascular treatment of chronic total occlusion of the subclavian artery is technically feasible, with a reported technical success rate of around 90% in one small series of 23 patients and 5-year primary and secondary patency rates of 75% and 79%, respectively (110). The rate of clinical symptom remission was 95% for technically successful procedures. No perioperative death or permanent neurologic deficits were observed.

Upper extremity interventions for vascular access-induced steal syndrome resulting from above-elbow disease have a high success rate, whereas interventions for below-elbow disease have much lower success rates, with more patients requiring secondary procedures and low long-term access site survival (36). The subgroup of patients who are good candidates for below-elbow interventions are male patients who present with rest pain and have larger forearm vessels (approximately 3 mm), short occlusive lesions (less than 100 mm), two-vessel runoff, and an intact palmer arch (36).

All contributors' financial relationships have been reviewed and mitigated to ensure that this and every other article is free from commercial bias.

Douglas J Lanska MD MS MSPH

Dr. Lanska of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health and the Medical College of Wisconsin has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

See ProfileNearly 3,000 illustrations, including video clips of neurologic disorders.

Every article is reviewed by our esteemed Editorial Board for accuracy and currency.

Full spectrum of neurology in 1,200 comprehensive articles.

Listen to MedLink on the go with Audio versions of each article.

MedLink®, LLC

3525 Del Mar Heights Rd, Ste 304

San Diego, CA 92130-2122

Toll Free (U.S. + Canada): 800-452-2400

US Number: +1-619-640-4660

Support: service@medlink.com

Editor: editor@medlink.com

ISSN: 2831-9125

Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Jul. 17, 2024

Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Jul. 17, 2024

Stroke & Vascular Disorders

Jul. 16, 2024

Stroke & Vascular Disorders

Jul. 02, 2024

Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Jun. 28, 2024

Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Jun. 21, 2024

Stroke & Vascular Disorders

Jun. 18, 2024

Neuro-Ophthalmology & Neuro-Otology

Jun. 18, 2024